By Octavia Findley

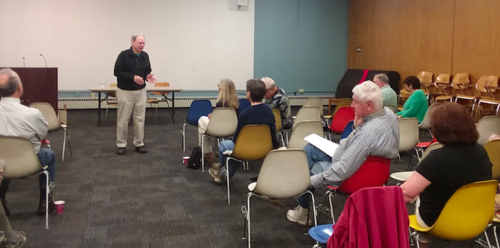

The scent of drip coffee lead me to the Large Auditorium of the Albany Public Library’s Washington Branch, the announcements for other events to follow were already being said over a thankfully moderate microphone. I sat in the back, politely declined the welcoming offer of further caffeinating myself, and reached for my pad and pen, ready to join the convivial space.

The topic of the weekly book review was A World Without Time: The Forgotten Legacy of Gödel and Einsteinby Palle Yourgrau, given by Jonathan Skinner, a retired statistician. I was not the only person in the audience thankful for his knowledge of twentieth century science, as he went on to explain the parameters of the book. He briefly discussed the main points of the book, pared down for the ease of layman’s understanding: relativity, the nature of infinity and time. Those ideas were complicated by formal versus intuitive calculations; the choice of the addition sign to denote mathematics or the simple observation that two plus two is four. This was not a scholarly tome in and of itself, but it was derived from such, as this book takes the more philosophical route in the explanation of how these two men became friends.

Both Kurt Gödel and Albert Einstein were European immigrants, but that is where the similarities begin and end, as Skinner explained in detail, “Einstein was Jewish, Gödel was Lutheran. Einstein preferred classical music, Gödel preferred light opera. Einstein was democratic socialist. Gödel was conservative. … They were neighbors in long walks around Princeton, discussing philosophy, math, politics, and everything under, over and beyond the sun.” Gödel’s proof, unsurprisingly, is related to Einstein’s theory of relativity, and explained in a way that raises more questions than answers: In a universe described by relativity, there is no time. Both Gödel’s and Einstein’s advances are mired in the movement of the mathematics and sciences of their day; their friendship serves as a marker for the era’s changing perspectives in the shift from nineteenth century certainty to twentieth century uncertainty.

A few questions were taken by Skinner, many he knew a better answer to, but did not have three hours, several chalkboards and his notes to teach from. “What recent ideas are now more present? I thought relativity does not discern what is real from what is true?” one attendant queried. Skinner answered, “As denoted by the author’s two separate accounts of the same two scientists, there is a difference between the nature of the physicist and philosopher’s goals.” Another asked, “Does closed system have anything to with entropy?” Skinner paused, unfolding and folding his hands, “Entropy is connected to time. There is no preferred direction to time even though by all of the grey hair in the room, we do prefer what is denoted as ‘forward’. There are many articles linking entropy to time, and most of them are denser than we have time for today.”

As if on cue, a volunteer came up and announced the end of the program, and the clicks of canes and rustling of purses signaled the patrons exit.