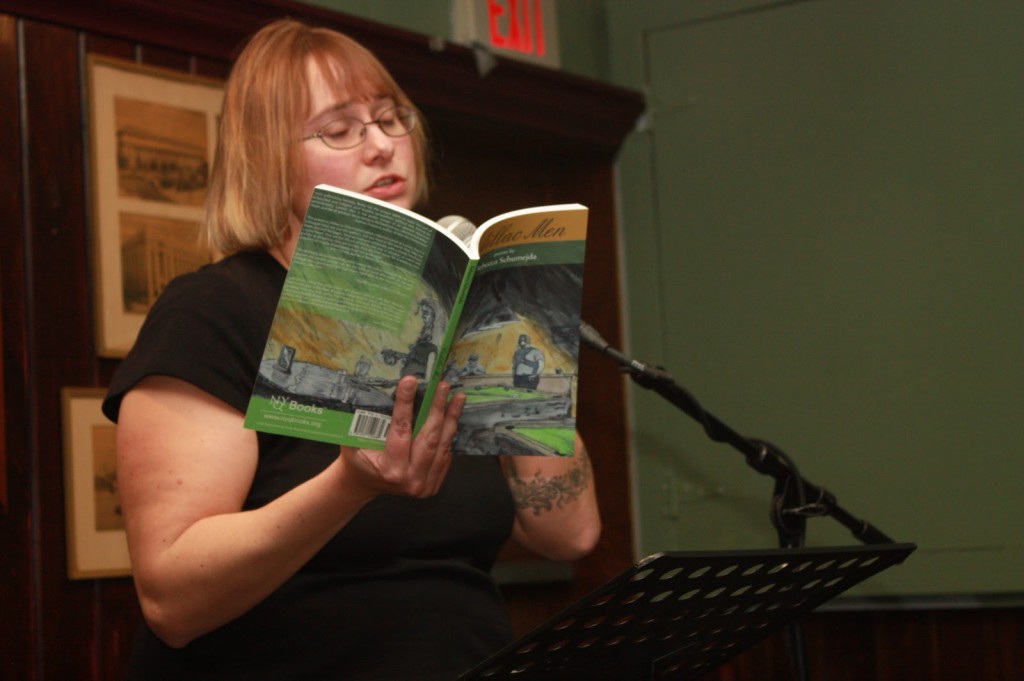

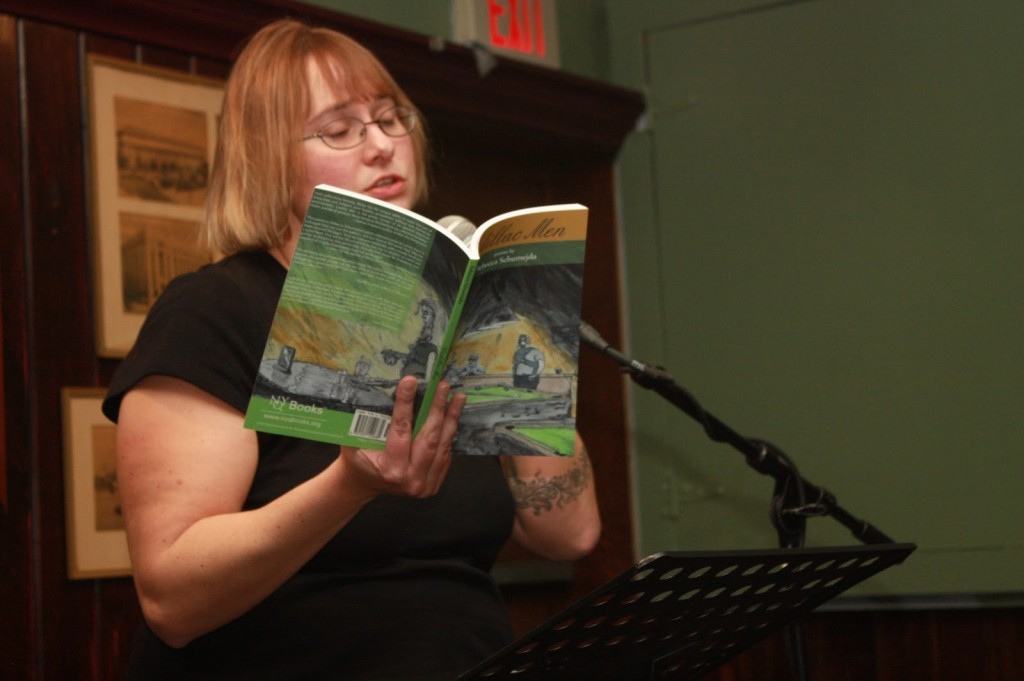

Rebecca Schumejda is the author of Waiting at the Dead End Diner (Bottom Dog Press, 2014), Cadillac Men (NYQ Books, 2012), Falling Forward, a full-length collections of poems (sunnyoutside, 2009); The Map of Our Garden (verve bath, 2009); Dream Big Work Harder (sunnyoutside press 2006); The Tear Duct of the Storm (Green Bean Press, 2001); and the poem “Logic” on a postcard (sunnyoutside).

How to Classify a Reptile

At the reptile show, I am reminded of him,

the first guy who made me orgasm.

As the presenter drapes a yellow Burmese Python

around his shoulders, I think about how my ex showed up

at my doorstep unannounced over a decade after he said

that I was like his Volvo, comfortable and dependable,

but not worth going back to once he’d driven a sports car.

Yes, he really said that and I said nothing, nothing at all.

Instead I cried every time I saw his new girlfriend,

his beautiful blonde Ferrari, everywhere I went around campus:

in the food court, at the library, throwing bread to the fish

that swam in the gunky water, playing the bongos outside the art studios,

and smoking clove cigarettes outside the Humanities Building.

While the presenter flips the python over so we can see

the snake’s claws, proof of evolutionary progress,

I think about how I let my ex in, how he sat at my kitchen table

while I peeled and sliced an apple for his daughter

and gave her a glass of milk with a red and white striped straw.

I listened as he told me his sob story about his custody battle,

about not having a job, living in his mother’s cramped apartment

that didn’t even have a bathtub. He even had to wear his bathing suit

to take showers with his daughter. Then he asked me if I had a tub.

I listened and poured him coffee. I made peanut butter and jelly

sandwiches for them while balancing my own infant daughter on my hip.

I did not offer up news about myself, I did not offer up our tub.

I listen as the presenter introduces Ally, a seven-month-old alligator

that the police took away from some guy who was keeping it

as a pet in his bathtub. This happens too much, the presenter says,

then goes on to say that a male can end up weighing up to

eight hundred pounds. He walks around the room to give the kids

a closer look. He explains how, like a submarine,

even when submerged under water, the alligator’s periscope like eyes

allow them to hunt for prey and I look away as Ally blinks at me

and think about how before leaving that day, my ex asked me for

gas money, and without hesitation, I reached into my pocket book

and gave him all that I had: a ten, a five and three ones.

(originally appeared in Rattle)

Our One-Way Street

We let our children ride their bikes on our one-way street at dusk

while we sit on dilapidated porches, discussing how our houses

are worth half of what we paid for them and make bets on whose

roof will go first. We all planned to fix them up, but found out

money is the only thing that leaves this neighborhood fast.

Out of the road! we yell when we see headlights.

I run into the street each time to make sure drivers slow down.

My neighbor to the right, Terry, tells me for the twentieth time

how while on a bike, he was hit by a car when he was my kid’s age,

rolled right over the hood, got back up and rode home.

Look, he says, holding up his hand, wiggling four fingers, I’m fine.

Patti, from across the street, donning a raggedy pink bathrobe,

asks, Did you really go to graduate school? with the same tone

you’d ask a coworker if they’re banging the boss. Shying away

from a response, I go inside to get a box of ice pops. Wine and

beer in big, red, plastic cups appear in our hands. Someone brings

out yesterday’s newspaper to show us an article about another

neighbor, busted for growing pot plants in his backyard.

It is too dark for the kids to see the chalk borders I drew

on asphalt earlier and we are buzzed, so the kids take advantage

moving further and further away from us. Their expanding

ellipses make me feel guilty about accepting another cup of beer.

Crazy Kay, the old lady who lives closest to the dead end sign,

strolls by with two of her stinky, old dogs, stops in the street,

screeches Who started the party without me?

As our kids circle around her, she complains about parking tickets

and the growing number of sinkholes in this city, If I didn’t know

better, I would say that this city is trying to swallow us whole.

(originally published in The Mas Tequila)