It’s a warm September evening, and I’m glad we’re out of the house onto the patio. Tess and I take chairs at the back as Dad and Mom and my aunts and uncles gather under the grape trellis between the back door and the garage. Mom’s passing around a tray of almond biscotti, but I can’t eat another bite after the dinner celebrating the wine making.

John Corelli picks a few grapes from under leaves covering the trellis and hands them around to the other men who still make a few bottles from their backyard vines. Their sons can’t or won’t help them make the 200 gallons Dad and Uncle Julio still do – with me and my son Nicky doing the heavy lifting. At sixty, I’m the good son.

Last week, I took Dad and Uncle Julio to the regional market. Like every year, they marched up and down the sheds covering crates of California Muscato and Zinfandel plucking a grape or two from the crates and making faces as though they’d bitten into lemons. I traded a shrug with the dealer who jokingly puts up with the old paisans who still manage to make it to the market, hauled along by a son who’d rather be golfing. Every year I think this will be the last one. Even with Nicky helping, old age, diabetes and a host of maladies keep Dad and Uncle Julio from drinking a fraction of the wine they bottle.

Nicky and I loaded the crates onto the trailer and hauled them to Dad’s cellar. Dad and Uncle Julio protested when Nicky pried off the slats and dumped the grapes into the press, but it’s been years since they were able to lift them. When they turned on the electric motor, they reminded Nicky how hard it was to turn the wheel of the press in the old days.

I remember the old days. Dad and Uncle Julio tossing the crates as though they were filled with feathers. Strong men, stripped to their undershirts, laughing and sweating in the low-ceilinged cellar.

The old men shift their chairs to one side of the patio. Dad leans close to John Corelli and Uncle Mario. They cackle and slap their knees.

Aunt Giulia says, “Pepe, get your accordion before these old men start telling stories we’ve heard for a hundred years.”

“I like the old stories,” Pepe says. “They’re the only ones I can remember.”

“Come on, Pepe,” someone calls.

“My fingers are tired,” Pepe says. “Too much good wine; too much wonderful food.”

“Please, Pepe,” a couple of the folks beg.

Pepe raises his hands in surrender and retrieves his accordion. He swings a chair around to face the others and plays a few chords.

“Quel Mazzolin di Fiori,” Aunt Louisa calls.

“Sempre,Mazzolin di Fiori” Uncle Tony says.

“It’s my favorite,” Aunt Louisa says. “I want Pepe to play it at my funeral.”

“You can sing it at mine,” Pepe says.

“Play, Pepe.”

Pepe starts with some chord flourishes. He begins to sing, and after a few moments, Aunt Louisa joins him. “Quel Mazzolin di fiori.” Haltingly, one after the other, they sing the chorus, “che vien dall montagna.”

I remember the words. This small bunch of flowers from the mountain.

My father and mother, aunts and uncles, cracked, trembling voices searching for the lyrics, humming when they’d forgotten. Urging Pepe to play one more favorite, they’ll sing and laugh until they fall asleep in their chairs.

My father puts his hand on Uncle Julio’s shoulder and whispers the next chorus into his older brother’s ear. “E guarda ben che no ‘l se bagna.”

“Take care not to get it wet.” Orphans. The two of them barely in their teens walking from farm to farm, working the fields, sleeping in barns, returning in winter to their home town where an aunt or a cousin would take them in until they set off again in the spring. Who would I have been if their uncle and aunt hadn’t taken them along when they left the old country for America?

The folks sing, “Mi fa pianger e sospirar.” He makes me weep and cry.”

“Are you all right?” Tess asks me.

I brush a tear from my cheek. “Tired. The old songs.” I nod toward the folks smiling at each other, singing. “They’ll be gone soon.”

Tess squeezes my hand.

I look at the glass of wine and take a sip. Maybe one more year.

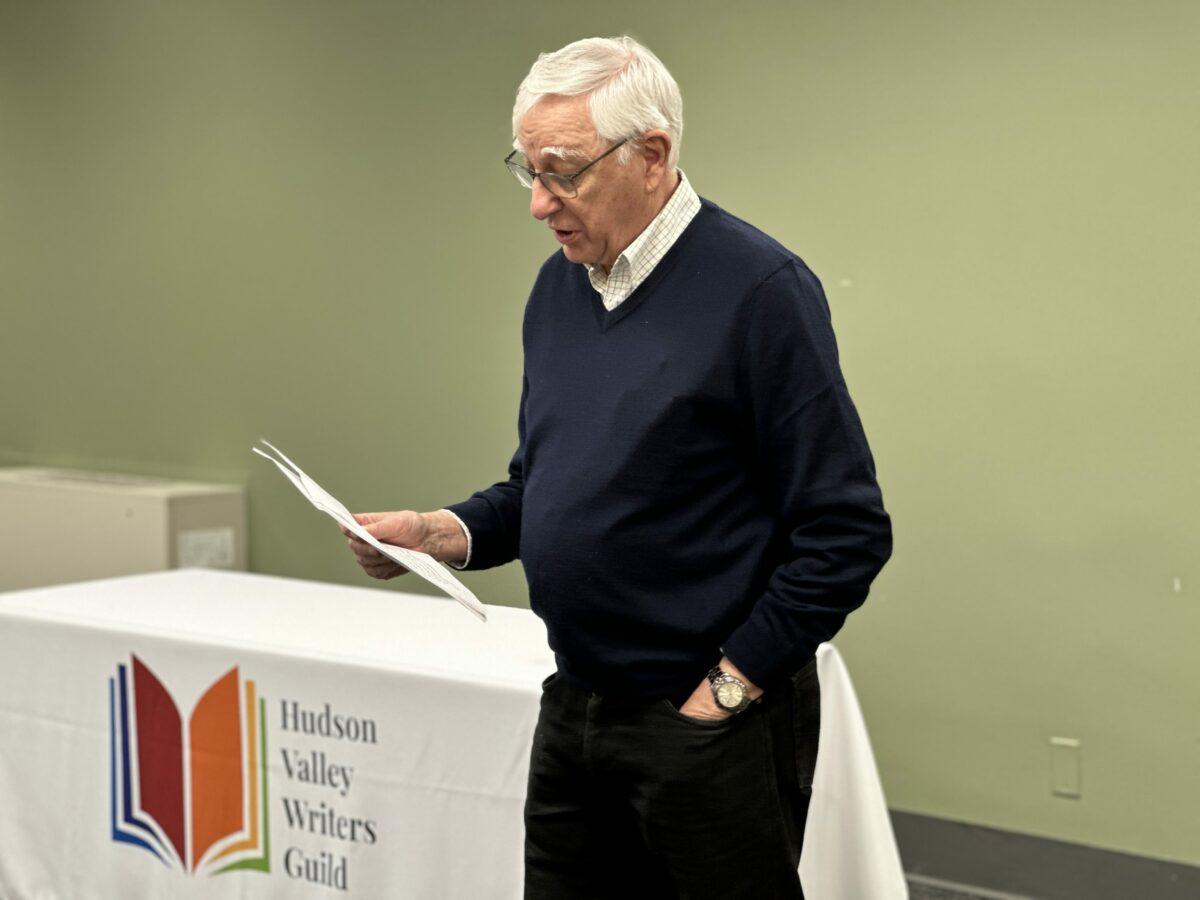

Paul Castellani is the author of four novels: Sputnik Summer (North County Books) is the story of a teenager whose testimony about a homicide rips apart an Adirondack resort town. Natalie’s Wars (Donwood Books) is the story of a woman who struggles through WW II on the home front and then with a husband psychologically damaged by the war in the years after; Marching On (Donwood Books) is the story of a woman striving to make a life of her own as she contends with the entanglements and competing demands of marriage, family, and friendship. The Prodigal’s Brother (Donwood Books) is the story of a man tangled in a family construction business that rode the housing boom of the last decade and implodes in the financial collapse of 2008 with deadly consequences.

Paul Castellani is the author of four novels: Sputnik Summer (North County Books) is the story of a teenager whose testimony about a homicide rips apart an Adirondack resort town. Natalie’s Wars (Donwood Books) is the story of a woman who struggles through WW II on the home front and then with a husband psychologically damaged by the war in the years after; Marching On (Donwood Books) is the story of a woman striving to make a life of her own as she contends with the entanglements and competing demands of marriage, family, and friendship. The Prodigal’s Brother (Donwood Books) is the story of a man tangled in a family construction business that rode the housing boom of the last decade and implodes in the financial collapse of 2008 with deadly consequences.

Before concentrating exclusively on fiction, as a researcher and teacher, Paul published a number of articles, chapters, and books on public policy. The most recent, “From Snake Pits to Cash Cows: Politics and Public Institutions in New York” (SUNY Press), was featured in several articles in The New York Times and The Washington Post. In addition to teaching in American colleges and universities, he received Fulbright fellowships to teach in Hungary and The Netherlands. For more background, see his website, Paulcastellani.com