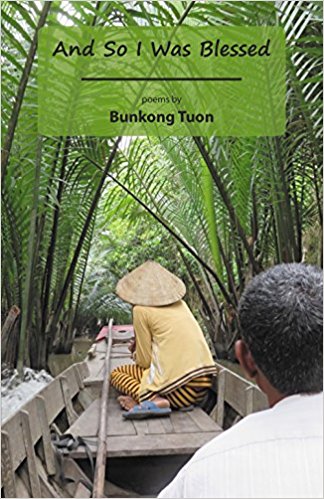

And So I Was Blessed by Bunkong Tuon

And So I Was Blessed by Bunkong Tuon

NYQ Books, 2017

97 pages

$15.93 on Amazon

At the crux of this collection is the journey of a son to his father’s village in the Mekong Delta juxtaposed with the father’s journey away from his own infant child. In “Daughter,” the narrator starts, “I must ask for your forgiveness/ for any mistakes I might make. I only want what’s best for you./ Remember, joy is not wealth,/ Which enslaves the psyche/ and destroys the spirit.” He continues to advise his infant daughter, knowing firsthand the emotional journey into adulthood, the way we are all fallible, how we often look for happiness in what we can hold in our hands instead of what we hold in our spirit. The narrator tells his daughter that “When lost, return to books,/ music, and arts,” a place of refuge. In “Stranger,” the last poem in the collection, the author follows his own counsel when he comes back from his own journey to a daughter who is unfamiliar with him. To soothe his daughter’s relentless crying, he takes out his guitar and begins strumming, which stops her tears.

The first two poems “Friend” and “Enemy” set the tone for the entire collection, in that what we assume to be true is often proven otherwise. In “Enemy,” a friend asks him why the narrator is going to Vietnam, since “They’re our enemy.” The friend goes on to explain, “The Khmer Rouge were/ trained by the Vietnamese./ Look at what they did to us!/ They may have Khmer bodies,/ but their minds are Vietnamese!” The friend goes on and the narrator thanks him for his thoughts, but the last line, the friend’s closing statement, highlights the irony of the exchange: “Just looking out for you, brother.” In “Enemy,” the poem that follows, the narrator shares a positive experience on the airplane with someone who by definition could be labeled his enemy. Although they didn’t talk too much, their silent interaction is touching, as noted by the narrator. “We ate quietly./ Then the woman touched/ my shoulder and held out a bowl/ of chicken salad.” Later he says, “She then reached into her purse,/ handed me a stick of gum,/ and smiled.” This poem sets up questions for a motif that surfaces in other pieces: Who is your friend? Who is your enemy? How do you tell the difference?

Tuon’s style which is straightforward narrative is filled with metaphorical gems like in “Searching for Father in Kampuchea Krom” #5: “Privacy was the mosquito net/ and the darkness of the countryside.” The narrator is the “nephew from America,/ in his forties and recently a father.” He is experiencing the life that his father experienced, he is seeing firsthand the disparity between two cultures and utilizes his poetic prowess to enhance his observations. The last line shows how unsettling the night was, “My father once slept and ate here,/ breathed this air, walked on this dirt./ The bed was hard, the pillows high,/ my back ached. I tossed and turned,/ wrestling with thoughts of him.” This section of the collection focuses on returning to his father’s homeland and meeting family, who tell the narrator stories about his father. They talk about hunger, desperation, what a father does for a child like in #12; the narrator writes, “My father got down/ on his knees,/ clasped hands over head,/ and begged them/ for a sliver of a victim’s liver/ so that I would not starve./While everyone was sleeping/ my father snuck into the kitchen,/ stole a branch of coconuts/ and buried them in the woods.” The coconuts that the father dug up to feed his child every time he was hungry seems the perfect metaphor for what a parent will do for a child.

The distress in the poem, where the narrator loses sleep thinking of his father, is also shared when the narrator thinks about his own daughter when away on a term abroad with his students, paralleling the experiences of the son with that of the experiences of a father. In “A Day in Saigon,” a meal leads to memories and in turn a feeling of longing for family. “A young girl/placed a dish of wilted/ bean sprouts and green chillies,/ an extra dish of my favorite mint: one that reminded me/ of a dish my aunts made/ in the Mekong Delta. With chopsticks I shoveled/ the noodles into my mouth,/ shaking off a sleepless night/ of missing wife and child.” Tuon artfully shows how a bowl of noodles can transport you back to where you want to be. In the end, it’s evident that the journey of the son has changed the new father’s perspective on blessings.