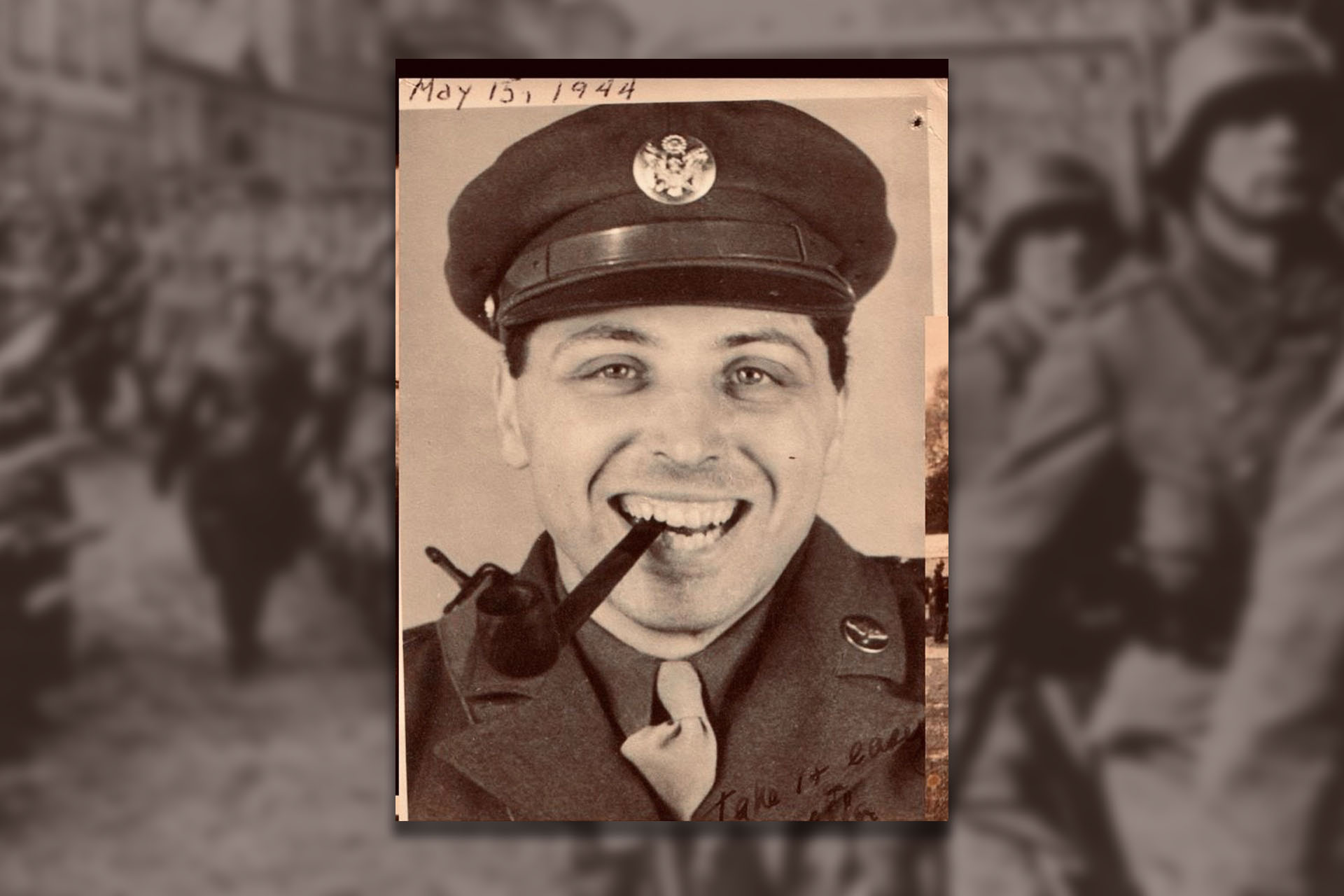

by Emanuel Soshensky with Rick Soshensky

Was it madness or Sanity? Maybe both, that freezing desperate night of December 21st, 1944 when a Third Army dogface and I, an Air Force photo interpreter, made our stand against the Nazi juggernaut behind a slightly-out-of-tune grand piano in a glass music room on the grounds of an abandoned castle in the Ardennes forest near Bastogne, Belgium.

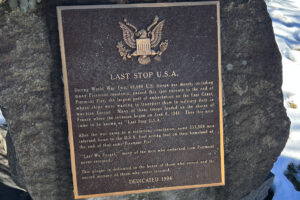

Late afternoon, December 20th, the open jeeps we were driving, skidded to a halt following a wild 125 mile ride, slipping and sliding along the icy, winding road, almost smashing into each other, trees, rocks and bombed out buildings, while at the same time keeping an eye out for snipers. My outfit, the 20th Photo Intelligence attached to the Third Army, had been on the move around Europe since July traveling through one ravaged town after another. Now, with the coldest Ardennes winter in living memory upon us, we felt good and lousy as we occupied the unheated, snow-bound chateau which was to serve as the gathering point for reinforcements and other tactical personnel coming in to prepare for the next phase of the battle – “The Battle of the Bulge,” – as it came to be known because of the shape of the land mass.

Antwerp, about 80 miles away, was a vital Allied supply port that Hitler intended to capture. This was Hitler’s last ditch attempt at winning the war and he was going for broke with every bit of manpower, weaponry and ruthlessness at his disposal. If he was successful, he could re-establish his domination of Western Europe. The Allies were just as intent on delivering the final blow but this was by no means a sure thing with our ill-equipped, inexperienced, frozen infantry, “dogfaces,” as they were called, suffering terrible losses at the front.

My outfit’s job was to analyze stereoscopic photos and recommend strategic bombing sites in the Third Army’s path. The pictures came from special cameras mounted on Mustang fighter planes that made three-dimensional images of possible enemy targets such as ammo and gasoline dumps, railroad yards, road hubs and, especially, troop concentrations and movements.

But right now all planes were grounded due to a thick, foggy overcast so it was hurry up and wait in the clammy chateau rooms assigned as sleeping quarters. After some cold K-rations and instant coffee heated on Jeep engines followed by a cigarette, we crawled into our sleeping bags, clothes and all. We were bushed but hardly asleep when the chateau was shaken by the hellish thunder and fireworks of an exploding Nazi

V-1 flying bomb as it was shot down by distant Allied anti-aircraft “ack-ack” fire. The V-1’s were Nazi robot planes, each armed with a ton of explosives and capable of flattening a square city block. The same V-1’s had devastated London and killed thousands as part of Hitler’s “rabatz,” his word for all-out, merciless terror he was unleashing in his attempt to destroy the will of the Allied forces. For the rest of the night, the chateau reverberated with the racket of the murderous flying bombs on their way to Antwerp and the Allied “ack-ack” guns trying to shoot them down before they got there. Exploding V-1’s shook the chateau like an earthquake. As far as any V-1’s that were shot down or might fall short of their target and land right on us, well, let’s just say we were expendable. Antwerp was not. It was that simple.

Hitler taking control of Antwerp would necessitate that the Allies launch another major invasion, possibly bigger than D-Day. This could take years, lots more men and might not succeed. After all we’d been through since D-Day six months ago, I felt like I might never see home again even if I lived which was doubtful. A direct hit by a V-1 would have crashed through the chateau’s solid roof and massive supporting beams as

easily as it destroyed block after square block in London.

As much as we needed the sleep, even short catnaps were barely possible. My cot was just below the lip of a window set in a couple of feet of stone. As I lay there, a near miss explosion shattered my window and sent the jagged glass shards zinging about an inch past my head, pitting the opposite stone wall and showering down on my cursing, scrambling buddies. Sonofabitch, I had lucked out! Those glass shards were worse than shrapnel. For some reason, my head was flat on the cot and not, as usual, on a pillow made up by my scarf and the wool cap I wore under my helmet. If my head had been a couple of inches higher on the pillow, it would have become one hell of a mess and my parents would have gotten a telegram from the War Department, $10,000 in life insurance from Uncle Sam and the right to hang a gold star in their New York City tenement apartment window.

After that hell of a night, the next day was relatively quiet. The people who had arrived before us said there would be no more V-1’s until nightfall so we got some sack time. For late morning chow, more cold K-rations with cold instant coffee this time because gasoline was precious. More lousy weather and more hanging around.

For some much needed reminders of home and peace, we listened to Armed Forces Radio as well as that traitorous bitch DJ from Ohio, Axis Sally, on Nazi Radio, who played American Swing music and nostalgic classics like Big Crosby’s “White Christmas,” or Dinah Shore’s “I’ll Be Seeing You.” This music was so essential to us that when Sally’s worn out copies got too scratchy to bear, some Allied daredevil pilot actually flew through heavy artillery-fire to parachute a few boxes of new records over her radio station. It’s funny how a song can become a lifeline in a place like this. Just the fact that somebody cared enough to write it, to sing it, that it exists at all, seems to connect with something innocent, something joyous. Something you can’t name, but man, we needed it. It came with a price, however. In between songs, Hitler’s DJ, as we called her, propagandized endlessly, cooing at us with her sexy voice not to die in a hopeless battle, telling us we’d be treated well if we surrendered and implying that some draft-dodger was probably back home making love to our girl and earning big bucks while we were here like chumps.

Sometimes we could laugh at her but sometimes she depressed us. We didn’t know what to believe anymore. We heard that in Malmedy and other places, thousands of panicking GI’s were being captured, herded into snow-covered clearings by the SS and shot. American speaking Nazi infiltrates took advantage of our shaky morale by spreading scuttlebutt about mass surrender and how Eisenhower and Armed Forces Radio were hiding the truth that it was now every many for himself. This was more than unbelievably frightening and disheartening. The thought that all this horror and bloodshed might be for nothing was unbearable.

The whole incomprehensibly fucked-up mess swam in my head as I walked out into the foggy twilight. It wasn’t a rational decision. The snow, already knee high, continued to fall. Nobody went out in the evening when the V-1’s were about to come. I just had to have some time alone with my thoughts.

Nature had always been a source of refuge and inspiration for me. As I slogged along through the endless Ardennes forest, gusts of wind made the trees sway, creak and crack; the fog imparting additional menace to the trees stark against the snow. Those noises – were they caused by the wind or by the skulking snipers in all white camouflage making them almost invisible against the snow? I released the safety on my M-1 carbine.

I discovered the music room in a forested knoll about 200 yards away from the chateau at the end of a winding path covered in deep snow. It was empty and quiet and so cold, the unheated chateau seemed snug by comparison. But the danger and discomfort seemed to momentarily dissolve in the peaceful solitude. In the center of the room was a badly nicked grand piano and a rusty jerrycan. The Nazis had stripped the room of every other movable valuable, just as they had stripped the chateau. I leaned my rifle against the piano, upended the jerrycan and sat on it at the keyboard for I don’t know how long.

The room was a circular, all-glass structure offering a 360-degree view of the surrounding forest. It had been a beautiful room, I imagined, in peacetime. Impeccably furnished, possibly with priceless antiques and its centerpiece, the grand piano finely tuned and polished. Fashionably dressed ladies and gentlemen, full of fine food and vintage wines, warm and safe, listening to a talented pianist playing Chopin, Liszt, Gershwin. Now bare of all artifacts of civilized living, it still provided a sanctuary for meditation; a brief encounter with something that made sense; something beautiful. The wrap-around glass walls muffled the ominous forest noises as I gazed at the living Christmas card of white snow, bare trees and icicled chateau roof topped with swirling mist.

Between long stares at the scene, my index finger began picking at the piano keys; some out of tune from the neglect and cold. I finally found the first four notes – three short, one long – of Beethoven’s Fifth Symphony. Three short, one long – the letter V in Morse code and the Allied symbol for victory. Three short, one long was flashed from planes and ships, played by orchestras and soloists before concerts and beat out on a bass drum on BBC broadcasts since 1940 when Hitler seemed unstoppable. My index finger kept tapping out three short, one long but now it was almost night. Soon the V-1’s would fall and I needed to get back to the chateau. I rose, picked up my carbine, turned and there stood the dogface, M-1 rifle in hand.

I scrutinized him in an extended split second. Germans in GI uniforms were everywhere. Who was friend? Who was foe? We had to make up our own passwords, something only a Yank would know. Something like “Halt! Gas-House Gang,” or “Halt! Brown-Bomber.” If the first answer was anything but the St. Louis Cardinals or the second anything but Joe Louis, the guy got it. I was about to point my carbine at him and challenge him with “Oomph Girl” to which the answer had better be Ann Sheridan, not Betty Grable or any other pin-up girl. But I did and said nothing. If he was a Nazi, he could have already shot me and escaped into the forest without anybody seeing or hearing anything.

I didn’t know how long he had been quietly standing behind me but he probably heard my clumsy attempts at music and I felt a little embarrassed. He was in full combat gear, as was I, his beardless face about nineteen but his eyes, tired, sad and resigned were 60. Eyes that bespoke the misery of too much war from the ground up. I was 26, not having had it as rugged as an infantryman and so, with four days growth of beard, I felt more like 50. He was so short, his rifle seemed almost as big as he, his helmet too large for his small head with long hair, his overcoat too long, his pants too baggy in his combat boots. I was a six-footer whose uniform wasn’t exactly Saville Row either.

He leaned his rifle against the piano, sat on the jerrycan, blew a steamy breath onto his fingers, hit the keys and three-short and one long.slightly out-of-tune but majestic chords filled the room. Beethoven’s Fifth resounding a goddamned V for goddamned victory! I put my carbine next to his and leaned against the piano. In the failing light, I saw his jaw set, his eyes narrow with concentration.

I was equally intense as, one after the other, he played songs like “Home Sweet Home,” “Home on the Range,” “I’ll Be Home for Christmas,” “Back Home in Indiana” – songs with home in them where he wanted to be as much as I did. As the dull roar of an approaching V-! and the ack-ack shells bursting around it vibrated the music room’s glass walls, he immediately launched into the popular wartime ditty, “We Did It Before,

We’ll Do It Again.” Through the crescendoing din, he played fighting hymns of the Army and Air Corps, while, with one ear, we listened for the sudden quiet of a “flameout” directly above which meant that we were the bullseye of a plunging V-! and had about ten seconds to live. As the sound of the V-1 passed overhead and receded into the distance, he played “Ave Maria,” and I thought Amen. Then he conjured good weather

songs like “Blue Skies,” “Sunny Side of the Street,” “Moonlight Sonata,” “It’s Always Fair Weather.”

When we heard another V-1 coming and the glass started rattling, he switched to fight songs. He kept playing them as the V-1 approached, sputtered and went silent overhead. Flameout! We were dead! I held my breath and the ten seconds seemed like ten years while the dogface played on as if nothing was about to happen. The V-1 exploded with a tremendous flash just beyond the chateau which partially deflected the

blast. The little room shuttered furiously but didn’t implode into a cloud of lethal glass. Without missing a beat, the dogface softly played “Ave Maria.” I thought, “Amen,” but then he swung into the Spike Jones novelty hit, “In Der Fuhrer’s Face,” the first lines of which go, “Ven der fuhrer says vee iss de master race, vee Heil! Heil! In der fuhrer’s face.”

This established the pattern of non-stop music that lasted the rest of the night, the out-of-tune piano seeming harmonious in an out-of-tune world. The dogface strung nostalgic songs together thematically, evoking our stateside heaven compared to this hell. Songs like “Roll Me Over in Clover,” Don’t Sit Under the Apple Tree,” “Shoo Shoo Baby,” “The Way You Look Tonight,” “Take Me Out to the Ballgame,” “Beer Barrel Polka,” “Silent Night.” Or he played classical and semi-classical selections; Bach, Stravinsky, Strauss, Offenbach, Ravel, Liszt. Timeless reminders of humanity’s nobility in contrast to the depravity all around us.

When the thunder of the V-1 and ack-ack’s began rattling the glass, he’d switch to fight songs. When the V-1 passed by, it was “Ave Maria.” If it exploded close enough to tremble the ground, it was “Ave Maria,” then “In Der Fuhrer’s Face.”

Against he night’s blackness shredded by fire, against the insane death-march percussion of explosion, gun-fire and rattling glass, rose the dogface’s music of rationality, beauty, peace and life. The last V-1 came over in a foggy dawn. It was an “In Der Fuhrer’s Face” V-1. After it hit and shook things up, the dogface played nostalgic songs for what seemed like a long time. Still no V-1. No ack-ack. Just an eerie calm. It got a bit lighter. Birds flew by. He stopped playing. We grinned at each other. Just like Hitler, we went for broke and we’d won out against his bloody “rabatz.” Music had the last word.

The dogface hit the keys. Four chords resounded through the room – three short, one long – even more stirring then they were about 12 hours ago. Standing up, the dogface rang out “Stars and Stripes Forever” then “The Star-Spangled Banner.” We both stretched, took our guns, patted the glass walls as we left and trudged through the snow to the chateau where we again faced each other. His sad eyes, no longer tired or resigned, were steady. He saw the steadiness in my eyes and smiled. We punched each other on the shoulder and went our separate ways to a breakfast of cold K-rations, cold instant coffee and a cigarette.

Hitler was finished. We endured the V-!’s again that night but the next morning was clear. The infantry moved out and the planes were airborne. Germany’s advance was halted and with their military resources depleted, they surrendered a few months later.

The dogface has never been out of my thoughts. I like to think he survived the war as I did and enjoyed the simple beauty of life we both yearned for through his music. We shared a mighty powerful omen that night and I wondered why we never said a word to each other. But then, what was to be said when there was perfect communion?

Rick Soshensky., MA, LCAT, MI-BC, NRMT, has been a music therapist for over 30 years. He is the author of the multi-award-winning book, “The Music Therapy Studio: Empowering the Soul’s Truth” as well as numerous published journal articles, and textbook chapters. He operates The Music Therapy Studio (themusictherapystudio.com) in his hometown of Kingston, NY and has lectured nationally and internationally. His work has been featured in The New York Times, National Public Radio, Spectrum News, Fox Radio and numerous other print, TV, radio and web media.

Rick has lived his entire life in the world of music, performed for the Queen of England and played on dates with Ella Fitzgerald, The Four Tops and other luminaries. As part of the New York City music scene in the ’80’s and 90’s, Rick wrote songs, recorded and performed throughout the country. In the mid-90’s, he shifted direction, enrolled in New York University to complete his Master’s degree in Music Therapy and began applying his talents towards the growth and healing of his clients.

Thank you for this recounting of your father’s experiences. Honors. Respect. Gratitude. Music to heal. Music to love. Music to empower. Keep shining.