Memorial Day

Finding your suitable match must be

something like finding happiness—

an out-of-the-corner-of-the-eye

kind of thing, killed

if you try too hard

at all. It must be, because

I’ve killed a few myself,

trying so hard I’ve often died.

Then those little deaths gather

for a little convention

over the three-day weekend, saluting

the limpid white flag you carry

in the Parade of Failures and teasing

graveside toasts to your attempts.

All you wanted was reunion,

your Aristophanic better half,

and to release the pressure

on your own weary one,

weary, it turns out, from trying.

If it had only known not to try

till it always died

it may have found its wholeness

in a repose supposedly

unsupposed to be noticed.

Personal Archeology

Imagine the graphable shifts

in your own self-civilization

from proud, young hunter

to calculating gatherer

to steady cultivator: industrious

over worker of your fragile

inner child. And notice

those thin but alarming layers

in your sedimentary record,

the relative moments indicating

odd breakthroughs, beneficial

mutations, weathered disasters—

in my case, that sudden thaw

of marital ice, the one that displaced

my psychic shoreline inland

hundreds of miles, submerging

remnants of a domestication

I’d survived in ignorant

and therefore precarious peace.

Any trained observer could write up

the reports, even poems

on the highlights. Why, I can recount

all kinds of particular days

like geological calamities:

when my grandfather died

and his wrist watch stopped

on the minute he hung his screaming arm

over the gunwale at the Red Umbrella Inn;

the first time I got drunk, so sick

on a buddy’s dad’s secreted liquor

I thought my life would spin forever

out of control; my wedding

when I served the wine, played crazy

blues harmonica and scatted us

on our merry married way;

the divorce.

So why, you may now want to know,

can’t I recall the eons in between,

those thick, bland strata,

those uniformly-striped piles of years

on years when nothing noteworthy

seems to have happened

but wherein must have developed

the insidious disintegrations,

and wherein I must have lived

over twenty thousand of my give-or-take

twenty thousand five hundred days?

Couldn’t Be Happier

How do I know I don’t need what I want?

I don’t have it.

—Byron Katie, Loving Reality

I couldn’t be happier, I’m saying

to myself this damp gray day,

late April, forsythia blazing anyway

across the street, rain dripping

from the porch roof eave, because

I’m not. Likewise, nine thousand

additional dollars aren’t called for

against the latest unexpected expenses

since they aren’t showing up, and thanks

and appreciation from the kids—hell,

from anybody—obviously aren’t in order:

none’s coming in. How do I know that

nobody should know that melancholy’s

returned? Nobody knows. And who

was ever supposed to think that shredded

shingles, general meanness, governmental

homicides, and this next pandemic shouldn’t

have appeared? They’re here! This drove

François-Marie Arouet de Voltaire nuts:

reality daring to define what’s real, this

best of all possible worlds, happiness

with what is. Try telling that to all

the bloody survivors, the skeletal ones

with victim mentalities who make

the nightly news do-able, the imbeciles,

like us, who can’t see the bigger picture.

Next thing you know they’ll be wanting

water, nutrients, UN intervention, still

not comprehending if they don’t have it

they don’t need it. Next thing you know

they’ll all be challenging reality.

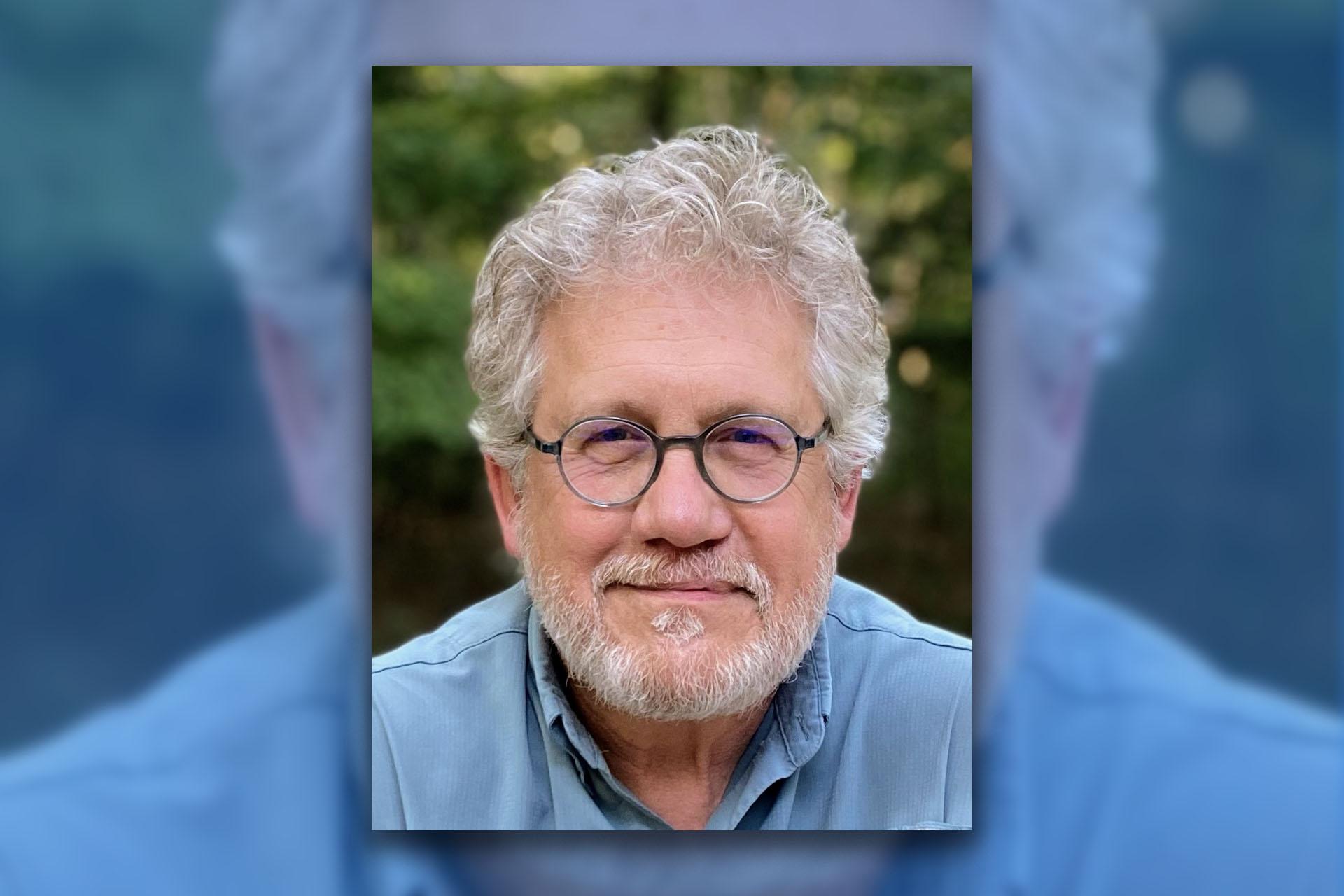

D. R. James, retired from nearly 40 years of teaching college writing, literature, and peace studies, lives with his psychotherapist wife in the woods near Saugatuck, Michigan. His latest of ten collections are Mobius Trip and Flip Requiem (Dos Madres Press, 2021, 2020), and his work has appeared internationally in a wide variety of anthologies and journals.