His supervisor interrupts his progress along the long line of tables against the library’s plate glass windows. The custodian’s busy scraping chewing gum off them when she clomps up. Pink, blue, and green blobs all stuck to their undersides. He uses a putty knife to pry off the dried, rubbery goop. Every now and then, out of some morbid curiosity, he imagines taking one of the globs and chewing it before throwing it into the bucket. Would it still have a hint of blueberry or wintergreen?

The supervisor walks on prosthetic steel legs. No one’s sure how she lost them, and no one wants to ask. The custodian imagines either a motorcycle accident or bear attack. He stops his rhythmic scraping to hear what she has to say. The supervisor habitually forgets his name so she reads it off the small, oval patch sewn onto his shirt. Roget, I have good news. Time for you to take a vacation, old dog. But Roget isn’t his name, and he isn’t an old dog, he’s only twenty-three. He doesn’t care that his name’s misspelled. He likes the name Roget. Roget’s Thesaurus is the title of one of the books in the library and this makes him feel important like he too has written something important in this important place. Maybe now, even though he has trouble reading, he’ll check the book out since his supervisor is making him take five days off. Good news, she says. They’ll be the longest five days of his life.

Five days he can’t clean the library. There are shelves to dust, bathrooms to clean, gum to scrape. Work for the supervisor and him. But most of the day the supervisor spends in her office downstairs, texting. And she can’t tear herself away from the phone. It seems like she’s always frantically tapping away on it, perhaps arguing with the girlfriend she mentions from time to time. Who’ll vacuum up the stray leaves that blow in from the outside when the automatic doors open back and forth every time a patron breezes through? Strapping the portable vacuum to his back, holding the nozzle in his two hands, he pretends it’s a flamethrower and the library’s under attack by deep state agents who want to steal all the books on 9/11. He smokes ‘em with glee.

What’s Roget going to do at home for five days alone? He has one friend Big Ray but he and Big Ray only get together every once in a while to watch the bass tournaments on Sunday morning television. Big Ray lives in the village with his wife and two kids Little Ray and Regina and drives a municipal truck and is usually too tired and broke to go out. Roget’s only other companion is his pet catfish he keeps in a giant aquarium. The catfish eats lots of worms and Roget has to go hunting at night to keep

up the supply. Roget pounds the ground with a stick. Worms rise from the muddy floodplain of the river. He holds twenty or more at once in his hand in a tangled ball because he likes to feel them squirming. They tickle and remind him of his mother circling her fingers delicately on his palm when he was a boy.

Why can’t he just tell his supervisor he doesn’t mind losing his vacation days? If that doesn’t work, maybe he could hide in the library past closing time and somehow sneak out in the morning. He could clean past dark with the lights off. He’d run his rag softly over the spines of the books, knobbly like the vertebrae in his mother’s back when she lay sick with lung cancer. It may be gloomy and awfully quiet, but he could always imagine the sound the school kids make as they come in for their afterschool programs laughing and teasing one another. What’ll he do with five days free at home but watch cable news and fear for the future?

Roget goes back to scraping gum. He picks off a piece, all black, sniffs it, and recalls the first and last time his father kissed him, the rusty tang and hot tar on a drunk’s breath. Then he remembers the friendly librarian who always greets him bright and early with Morning Roger! before she proceeds to the bathroom to secretly vomit up her breakfast. If he must take the leave, he’ll be sure to tell his supervisor she has to scrub the toilets the very first thing.

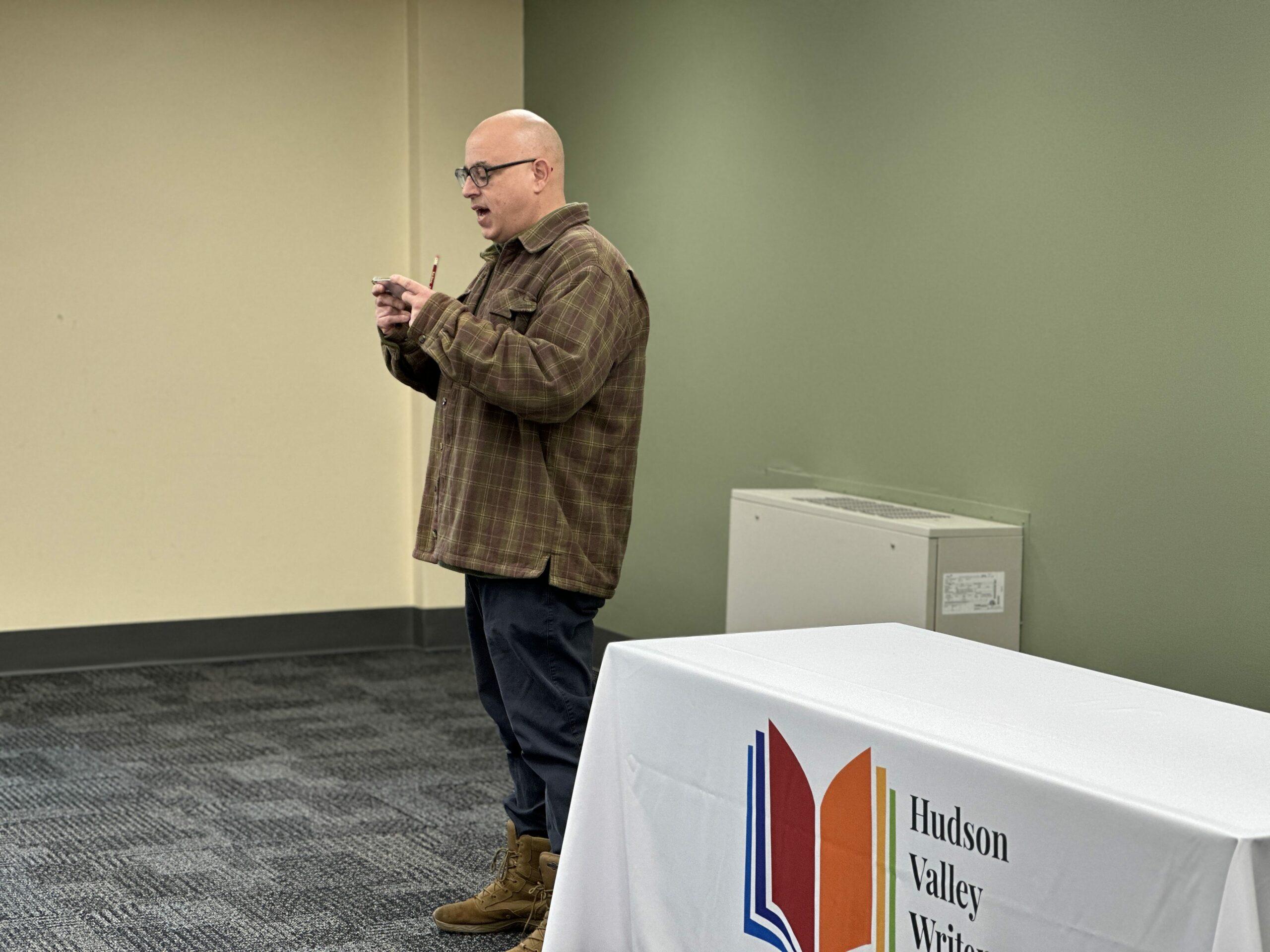

Alexander Perez began writing and publishing poetry in 2022 at age forty-eight and is a Hudson Valley Writers Guild member. Alexander currently lives in Schenectady, New York, with his partner James. Read more of Alexander’s poetry at perezpoetrystudio.com.