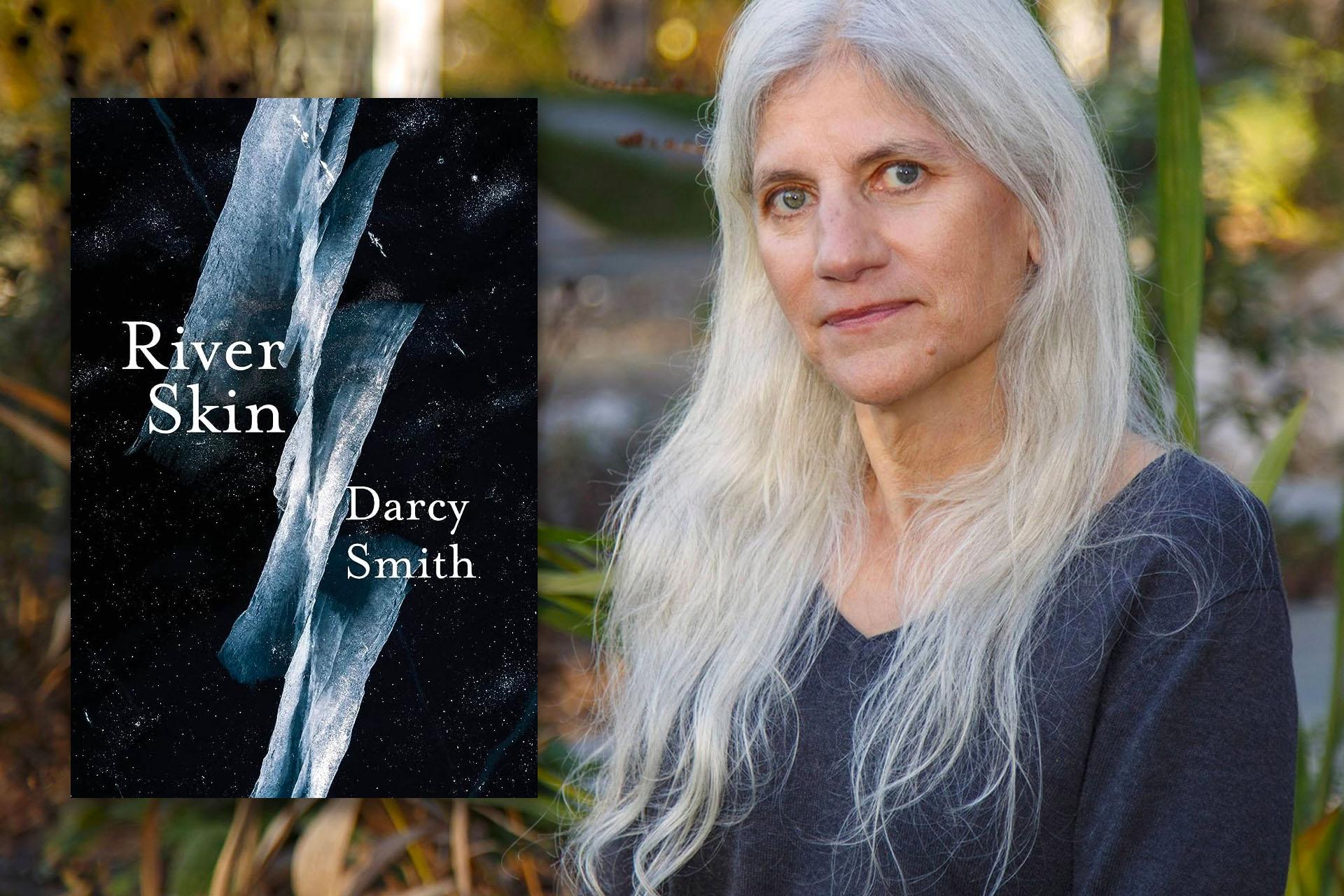

Darcy Smith’s River Skin (Fernwood Press, 2023) makes me think of Emily Dickinson’s definition of poetry, the only definition I believe to be the truest measure of what poetry is and does. In a letter to Thomas Wentworth Higginson, who became her mentor, Dickinson says, “If I read a book and it makes my whole body so cold no fire can ever warm me, I know that is poetry. If I feel physically as if the top of my head were taken off, I know that is poetry. These are the only ways I know it. Is there any other way?”

Do we need another definition of poetry? I don’t. All I need is poetry that proves that the statement is true. I’m not comparing Darcy Smith to Emily Dickinson as a poet because no poet can compare to her. I am saying that so many of the poems in River Skin coincide with that definition.

For me, the best poetry always presents the unexpected, always unfolds in surprising images, phrases, subject matter. These show up over and over in these poems. Listen to the first stanza of “Your Lilacs Nest in Me.”

I give you a constant breath behind

the door. I give rusted hinges,

unsprung locks. I give you my sprig of lilac.

I give you the earth breached. I give you endless,

hopeful, airless heat. I give you the waning sun.

Try this: think of what else could be said at the end of each line. Try to predict what comes next as the opening of each subsequent line. Difficult, if not impossible to do. You can’t predict how each image plays out. “I give you the earth breached.” What a wonderful surprising image. And later in the poem, referencing Van Gogh, she says,

. . . And if he speaks only motion, as if you

speak me inside his needled light,

inside his cell, inside San Remy, inside my thinning

silence, inside his cypress. He brought bird nests in the hollow

of night, he was twigs breathing, he was saliva

from a robin’s breast.

The accumulation, the layering of images, the repetitive phrasing and of the word inside shows a mature poet giving us moment after moment of wonder and, yes, surprise.

“Punto in Aria” demonstrates brilliant moments of skewed syntax and layered possibilities of meaning in short lines:

We left parchment

nights stained

screams inside

fingers, folded wishes.

These brief lines offer many choices. How do we make sense out of “We left parchment”? Does this image stand alone or does it connect with “nights,” as in “parchment nights”? Then think about “nights stained” or “stained screams” or “stained // screams / inside fingers” and so on. Whatever the poet intended is inconsequential because the reader has to make the decision about what such lines mean by linking images / words or just accepting each brief line as a unit all by itself. Either way, what is stated offers more than enough to make such poems work. You have to get used to skewed images in River Skin because so many poems talk this way.

As a counterpoint to quirky lines and images, Ms. Smith offers up beautiful, straight to the point language as well. I think my favorite poem in the book is “After I Fell,” a love poem with a beautiful ending:

At our friend’s memorial, we danced in church, in yesterday’s incense, in prismed

light, in front of Mary, even if we shouldn’t have

–we danced.

To say I’m jealous of such fine images, is to admit I wish I had written such lines. To say I’d steal them, if I could overcome the guilt of having done so, is to admit my own shortcomings. To have this book offers a chance to find what we need on any given page. Read the book, then reread Emily Dickinson’s definition of poetry and see if I’m wrong about River Skin.

You can get your copy of River Skin on Darcy Smtih’s website, Amazon, and Fernwood Press.

Robert Harlow holds MFA and PhD degrees. He taught literature and writing for many years at the University of Arizona and the University at Albany. His most recent book– “Places Near And Far”–was published by Louisiana Literature (2018). A former professional stilt walker, he lives in the woods somewhere near Albany, NY.

This message is for Darcy Smith. I worked at Burger King with her in the,late 60’s