Q. In “Break Room,” you write, “it was in these places that I would/ unfold lined paper and scribble/there was always/a stopwatch ticking in my head/and there was always/ a co-worker wandering in/who wanted to know/what I was doing.” Can you talk about how you came into writing?

I was always a heavy reader, even in grammar school. Pop novels, not YA or poetry. My mother kept a steady stream of Stephen King around, that kind of thing. As a teen, I remember going on a break at some terrible fast-food job and I started writing verse on the back of an order ticket. It was a compulsion because at the time I wasn’t interested in poetry. By then the family unit had imploded, and there was great sadness. Maybe that had something to do with it. I can’t remember what I wrote. There was some journalism in High School, but I was more into music and movies. I worked a bunch of shitty jobs, entered the English program at Long Beach State and worked more shitty jobs. I took some lit classes with Gerald Locklin and he really opened my eyes as far as to what poetry and literature could be. I started reading Edward Field, Charles Harper Webb, Raymond Carver, Gerald Haslam and Bukowski, of course. And I kept reading and working shit jobs.

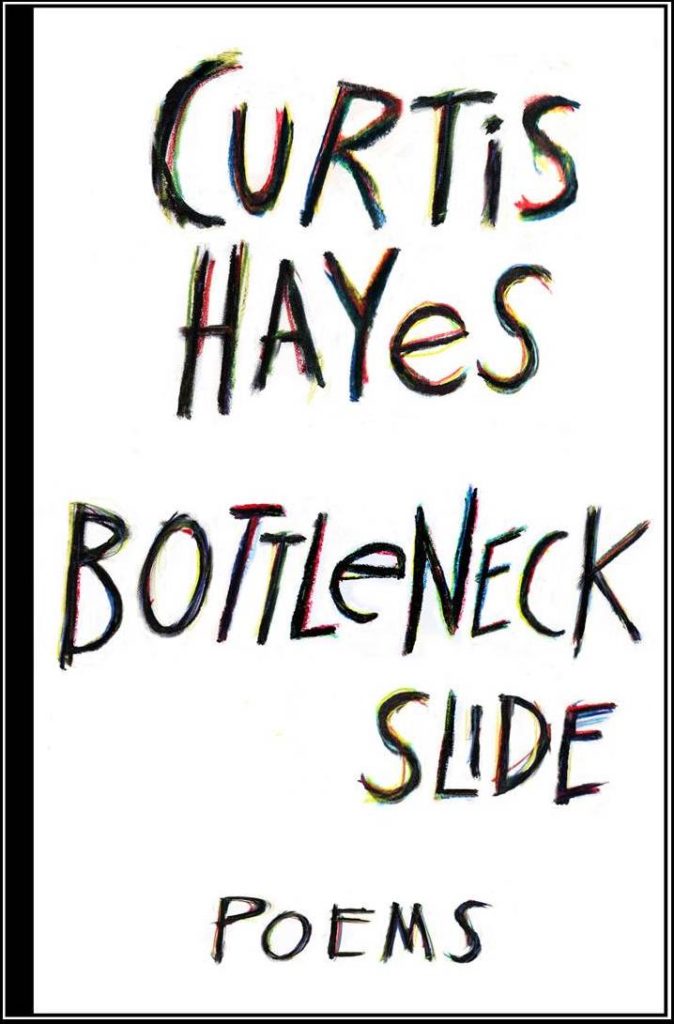

Q. There is a sense of place in so many of your poems in BOTTLENECK SLIDE, can you discuss place and how it has influenced your work?

Q. There is a sense of place in so many of your poems in BOTTLENECK SLIDE, can you discuss place and how it has influenced your work?

You know, Los Angeles isn’t really a city in the way that Chicago and Seattle are cities. When we talk about L.A. we’re really talking about the Southland, this dense concentration of concrete and people that stretches from the ocean into the desert. I would say that I fit into this place starting as a kid that was equally obsessed with skateboards and the Black Dahlia murder. I missed out on the whole beach culture funtime scene of the 60’s. As a kid I was aware of the Mansons and I remember watching the SLA shootout live on afternoon TV after school.

I’ve always lived a sort of nocturnal life. A lot of music in bars and nightclubs and driving after dark. When your only time off is at night, that’s when you have to live your life. Things shifted once I started working in the filmworld. Suddenly instead of four walls somewhere you don’t want to be, there is all this access to normally closed-off places. You are shooting up on the roof of a skyscraper all day, or inside a 100 year old theater where Fatty Arbuckle shot his comedy shorts, or you’re out in the Mojave, or in the old spanish-style postal annex next to Union Station; only now the upper floors have been dressed into a police squad room and there are perfect looking actors in uniforms and you’re wondering how much a certain L.A. poet hated coming to work at this place in years past. And then I’m hired to write a feature film, then a second one and all the words that had been rattling around in my head become dialog and action and I’m happy for the first time in my life- or as close to happiness as I’ve ever been. Then it all goes away because there is no permanence here and I’m back pushing lights and counting C-stands and-and-and. And I’m alone in my yard with a yellow pad of paper and a fresh gin and tonic and I watch the skinny shadows of two palm trees move slowly across a cinder block wall, as the sun spins overhead.

Q. Many of your poems start with work and then expand into other ideas/thoughts like in “My Vegetarian Summer”, when you start off, “I was driving a cab over bobtail/delivering lumber to construction sites/ while trying to scratch my way through/ and English degree at state,” and in “There Are No Rich Beverly Hills Women,” you begin, “it was quitting time at the boat dealership.” How has a working life shaped your perspective as a poet?

From my teenage years, I have been living without a safety net. So work was and is a constant and sometimes I couldn’t be picky about where my next dollar was going to come from. I learned early-on that most people really don’t want to pay you for your time. Your employers don’t respect you. You are forced into situations with people operating on a low level. I was always an observer and I paid attention, thinking that eventually I might be able to translate this journey into something worth reading. Once I snuck into the film business, things got better but not easier. Working on a set is chaotic and strenuous. You’re tired all the time. But you are doing interesting work and the people around you are often interesting. The thing is, no matter where you earn your money, there is class war and there is ego and narcissism and loyalty and betrayal and hopefully some camaraderie mixed in. What no one has anymore is security. The 2008 economic collapse changed everything and the filmworld was not immune. There has been no recovery for the working class. This lack of basic security affects everything I write. Driving through L.A. and seeing tents under every overpass is all the perspective I can swallow.

Q. Sometimes I feel like I get closer to people through poetry and in “White Castle,” I feel like you do just that, can you talk about writing about intimate relationships?

I guess like a lot of poets, I feel like people- even those close to me- don’t really understand what I’m all about. I’m kind of an old-school guy and as such I’m not one to discuss my intimate feelings with people. My father was a likeable and successful man who came from nothing and made something of himself. My relationship with him was very complicated. Maybe using poetry as a confessional is a way to express things that I don’t want to talk about. Or maybe “White Castle” just a story that I wanted to tell and it chose to unfold itself in terms of intimacy. Chiron Review first published this piece and Gerald Locklin ended up nominating it for a Pushcart Prize, so I like to think of this one as my father’s final gift to me.

Q. In “Ink,” you write: “The thing is, I never went to war./I never stumbled drunk through a Manila back alley on shore leave. I never won the big game.” Even so, if you were going to get a tat, what would it be and why?

You know, at one point I was dating this… hardcore woman. A real black-haired, slinky, femme fatale type- like she just walked out of a 1940’s crime film. She was the hippest one in every room, smoked unfiltereds, drank Campari, knew all the blues musicians in Hollywood- all that. I once asked her, “Why don’t you have any tats?” She came in close and growled into my ear, “Because I don’t NEED any tats.”

Q. So, if you didn’t respond to the last question and even if you did, if you went out, got shit-faced drunk with friends, and woke up in the morning with a tat, what would the that be?

Probably “BE YOUR OWN HERO” across my forehead in heavy gothic lettering.

That’s what I got, if you want me to rephrase or you want me to add anything, let me know…. Also sometimes I will think of other questions or you will answer and I will want to ask something else, so I hope that is cool!!!!

Curtis Hayes has worked in sawmills, pizza joints, and as a grip, gaffer, and set builder in film production. He’s been a truck driver, a boat rigger, a print journalist and a screenwriter. A Southern California native, he is a graduate of the California State University, Long Beach, Creative Writing Program and his poetry has been featured in Chiron Review, Trailer Park Quarterly, Cultural Weekly and other small presses. His first full-length poetry collection, Bottleneck Slide, has recently been published by Vainglory Press.