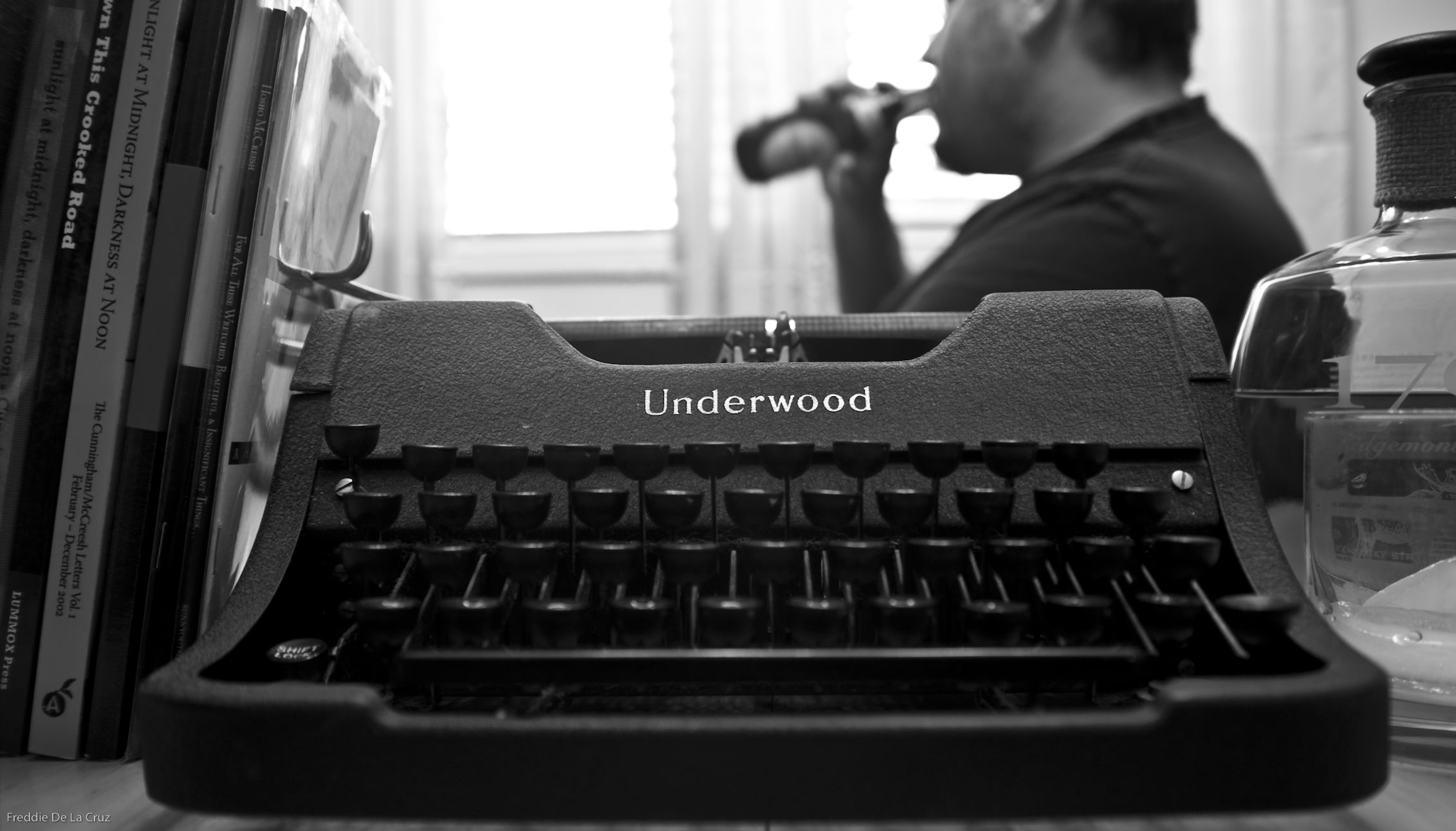

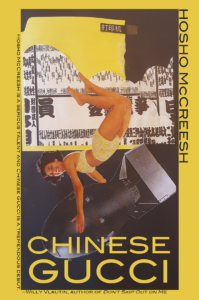

Interview with writer and artist Hosho McCresh, whose first novel, Chinese Gucci is forthcoming.

“To keep moving forward as an artist, you have to push, and flail, and fall, and recover.”

Q: What was the process of writing your first novel like compared with writing a collection of poems?

A: Very different. I’d tried to write novels over the years, and for whatever reason, I just couldn’t manage it. I’d get about 100 pages in, and have no idea what I was doing or why I should even care. At that point the only thing to do is scrap it all.

The main difference for me was the sheer number of hours and ideas you need to make a novel fly. I gathered ideas for years before I finally felt like I had all I needed to try a first draft. That’s a bit counter-intuitive for a poet. With poetry you want the idea, the one image or line that catalyzes the whole poem. There’s so much space in a novel that even when it comes to your core themes and ideas, they have to come back in, and fade away, then return — they’ve gotta be threaded through the whole thing. Plus there’s just a lot of logistical heavy-lifting to do — keeping timelines, and specifics consistent throughout. That stuff is easy to lose track of. It was all great practice, though. To keep moving forward as an artist, you have to push, and flail, and fall, and recover. And as a small press writer, I just happened to be in exactly the best place for it. No one wanted anything on a hard deadline, no one was waiting on me, or waiting on a manuscript…so I was able to keep tinkering until finally I had something I was proud of.

With poems, they bang around your skull until you write them down…then that’s it, they’re out, and there’s space for more. With a novel, it’s in your bones until you get it right.

Q: I had a love/hate relationship with Akira throughout the book; he is definitely a modern-day Holden Caulfield. Can you talk about your inspiration for this character?

A: I started out wanting to understand a few things about being young and brash and sure you know every damn thing — as I had distinct memories of feeling that way when I was young. It had something to do with growing up as a young man in America. Culturally, this kind of attitude was not only valued, but celebrated. So that was where the book began for me. When I was 11, 12, 13 — I knew it all. Then life started hacking it away, bit-by-bit.

Not coincidentally, when I was around that age, my mom was diagnosed with cancer, and got very sick. I started to wonder what could’ve happened to me, how different my life would’ve been had she not survived. Sprinkle in some gangster rap, and a crass imitation of the American Dream, and the book just came to life. Akira started doing all kinds of things, and I just tried to keep up. He was truly the reason I was able to finish writing the book. He was such a shit, such a royal pain in the ass — and yet, deep down, I just knew I couldn’t quit on him.

Q: Why did you choose to write from the third person point of view and what were the advantages and the challenges regarding your choice?

A: I think it had something to do with that specific degree of separation, and distance, and alienation you can find in the 3rd person. Akira is split right down the middle — half the time he thinks he’s in control, and the other half he insists he’s the victim of the cold, uncaring world. So which is it — are you calling the shots, or is shit just happening to you? It can’t be both, right? I think the separation, the distance — it was exactly the way to tell his story…as he, in many ways, is a stranger to himself.

Q: You begin the novel with a pretty risky scene (and I don’t want to give too much away, but…) Why did you start here?

Q: You begin the novel with a pretty risky scene (and I don’t want to give too much away, but…) Why did you start here?

A: First, I want to absolve Joshua Mohr, whose Decant Editorial I worked with on the almost-final draft, of any responsibility here because he absolutely warned me not to start the book like I did!

To me, there’s a couple things that need to happen immediately in a book, a movie, whatever — to both set the stage not only for the story itself but for the audience too. It should be memorable — that goes without saying — and it hopefully lets the reader know, in an instant, where the character is coming from.

As a beginning and as a short scene, it perfectly encapsulated Akira for me. It also lets the reader know just what kind of book they’re in for — which, as a reader, I’ve always appreciated. In terms of the story on the surface, and the dark undercurrents the book aims for, it felt like the right place to jump in.

I’ve always felt readers will either love the book, or absolutely hate it. Might as well start everyone deciding on page one, right?

Q. Can you talk about the purse as a symbol -I think it carries the weight of the catcher’s mitt in Catcher in the Rye?

A: Yes, Chinese Gucci. So — an expensive designer purse…but a fake one, then. Without tipping my hand too much, I will say that one of the main themes at work in the book is both the idea of something or someone, and the reality of it — and how rare it is when they’re the same. The world is absolutely inundated with the image, with the idea, inundated with facades. But the simple truth of things — be them people, ideals, countries — is usually far less glamorous, and far more sinister.

Q. Nita is a minor character, who I really want to know more about, I almost feel like she deserves to be the star character in a novel, can you talk about how you developed her character? I feel like you gave just enough to create intrigue.

A. You’re not the first person to say so! Yes, in terms of screen time vs. bang-for-your-buck, Nita is an absolute anchor. Her story would make a helluva novel. Let’s hope I’ve got the juice to write it someday!

In terms of how she was developed: it was one of those lucky moments when, as a writer, you stop looking at what you’ve already got on the page, and instead glimpse what’s missing. Again, it was Josh who helped confirm for me that something obvious and critical was missing from the book, something key to resolving it. I think we had maybe a two-minute conversation about it — and the next day I sent him a rough sketch of Nita. It was just so obvious, after we’d discovered her, that I truly didn’t know how the book existed without her.

Seriously though — if you’re fighting with a draft, and you know Josh’s work, and think he might understand what you’re after — hire him. Decant Editorial. Chinese Gucci became the book I always meant it to be thanks in no small part to Josh’s insights.

Q. You do a fantastic job of concealing the death that Akira is dealing with, which causes the reader to rethink him as a character more than halfway through the novel, can you discuss this decision?

A. There’s this thing that happens, even in good books, and good movies — where, in the interest or even insecurity of freighting some information to the audience, the characters just randomly start explaining shit. It drives me batty. I call it, “Talking to the Urn” and it makes me so crazy that I’d rather risk people not understanding what’s going on than to lay something out so nakedly.

Miles Davis knew the importance not only of the notes he played, but of the space between the notes — how silence is often its own powerful note. In poetry, in writing, in painting and visual composition, what’s not there is every bit as powerful as what is — sometimes even more so. I just felt that, at no point in the story would the actual people, all of whom knew the situation prior to the novel’s opening, randomly force some clumsy conversation about something everyone already knew. So, to me, it wasn’t really a decision at all. In dialogue especially, people rarely talk about what they’re actually saying. And certainly not when it comes to the big and difficult stuff.

Q: Do you see revisiting these characters the way that Salinger did with the Glass family?

I’m certainly not against it, but we’ll have to see. In the past five or six years, my writing has been very focused on just a project or two at a time, and I work only on what demands I work on it. In 2008, I started gathering material for five different long fiction projects. Ten years later, I’ve finished one. If Akira, or even Nita showed up with a whole novel’s worth of ideas, maybe I could just disappear into it until I had a draft. I really don’t know. Every time I think I have it all worked out, a project or an approach will grab hold of me, and I’m gone…dragged along in the current. But I’ve managed some books I’m pretty damn proud of, so I think I’ll stick with what’s working.

Q: Okay, so I have always considered you an enigmatic author, much like Salinger, can you speak to your choice of being more reserved as far as your author presence?

It’s mainly out of necessity, I think. I’m pretty much split right down the middle: half introvert and half extrovert. It just depends on the day, on where my head is at any particular time. Knowing this about myself, I know that — on days where I don’t want to be a writer, an author, a presence, an anything (because, honestly, most days, I’m not) — it’s better to just protect my privacy.

I’d say the only real difference between me and most writers is a few random photos on the internet. I guess most days I just don’t think I’m that interesting, and photos kind of embarrass me. You say, “enigmatic,” I say, “boooooring!” But on good days, days when I am feeling okay, and I’m surrounded by a bunch of my closest people — I’m a lot more engaged, and a lot less boring. I prefer being in small, close-knit groups, talking on a more intimate and meaningful level. I have to work hard to enjoy a big room full of strangers and surface-level conversations.

Q. Can you talk about publishing and why you decided to go the way you did with this particular project?

After finishing the draft with Josh, I tried to get an agent, and submitted the manuscript to a few presses I really wanted. It was a year’s long process that, honestly, is about as terrible as it gets. You exist in this constant state of tenuous hope and crippling self-doubt. It frays the nerves down to old rope. I got tired of it, but wasn’t really sure what I was going to do. The ego is a brutal master, and it had convinced me that the only way the book would matter was if I sold it to a press, or an agent did. So despite all the rejection (reference here: that risky opening scene), I didn’t know what else to do.

In the meantime, I’d taken up collage. It was something I’d never really played with, and I was immediately drawn to how a random smattering of images gathered up, cut out and pasted together, can become more than the sum of their parts. Now, it’s important to know that — at this point — there was still a lot in the novel that was more instinctual than intentional. I mentioned how Akira was what kept me writing. Well, as I was writing, I didn’t know why certain things had to be a certain way — I just knew that they did. I didn’t know why I had all these stray, albeit very specific, references to WWII and fake designer purses, and Juarez, Mexico — I just knew that certain things had to be part of the book. So, as an experiment, I decided I was going to try to do some collage work, to explore the deeper themes of the book visually…and it changed everything. Or, it revealed everything. I suddenly knew, and could articulate the whys and the hows of all this instinctual stuff in the book…clear as day. That’s when I realized I was writing a kind of secret American allegory instead of just a novel.

When that happened, I immediately saw hardbacks with original collages for covers, and I knew I had to put the book out myself, my way. I actually felt a tremendous sense of relief when I got my last rejection! Suddenly I didn’t want anyone to buy the manuscript and tell me I couldn’t do my collage covers! And, as a book that will probably be divisive, I felt a lot better about bearing the financial risk myself. I knew I’d hate for a small press that was just scraping by to dump a bunch of resources into my book only to have it tank and cripple them. To me, the strength of the small press has always been what it can do that big houses can’t. Sure, they can reach millions with their manufacturing and their media contacts and savvy — but no big press anywhere could do one hundred thousand hardback copies with collage-covers hand-made by Stephen King! I couldn’t either. But I can do 26. So the best way to put out exactly the book I wanted to was to find all the help necessary to just do it myself. It’s been more work than I ever imagined, but easily as rewarding as anything else I’ve done. For me, for big books, for interesting projects, this is absolutely the way forward for me.

Q: You are an amazing artist as well as one of my favorite writers, can you talk about how being an artist influences your writing and vice-versa?

Art and writing for me have always been two sides of the same coin. I have the same kinds of approach and rules for both — normally I start loose, and easy, never forcing anything, and just doing work when I feel like I’ve got the juice for it. But then, as a piece gets more refined, I start to invest more consistent time and energy into it, and work at it until it feels like the best I can do. I also don’t look to repeat approaches and ideas too much, so like-minded things, be them poems, pictures, etc, generally come out of the same time and era, and projects are constrained a bit by that. It’s harder with painting, as it takes a lot more preparation, having materials squared away and ready to go…so the eras and time frames of similar paintings stretch out a lot longer.

As for the novel’s cover: a lot of the collages I made for the hardbacks could’ve been the cover. The Advance Reading Copy actually had a completely different cover. I even made some collages, early on, that — size-wise — wouldn’t work as a hardback…and they could’ve been the cover too. But this piece in particular had a lot going on thematically that tied directly in with the book. There’s the glamorized, and sexualized image of a woman; there’s the WWII imagery, and what it still says about America and Japan; and there’s the fact that the story the picture is telling — that everything is fun and sexy and fine — is in direct contradiction to the reality: that this false, idealized beauty is laughing as she plummets to her demise. It seemed to really work well visually.

Q. What projects are you currently working on?

I have a couple projects lined up that I’m looking forward to devoting more time to. You’ll recognize the first: an unabridged audiobook for A DEEP & GORGEOUS THIRST. Because the poems don’t have titles, to make the audiobook work I needed a new reader (you for a few of them!) for each one. I reached out to family, lots of friends and folks in the small press, musicians, and after years, almost have recordings for every poem. So that’ll be a focus in 2019, trying to get that done. I have a short story collection, Bull Calves, sitting with Bottle of Smoke…and all those stories are also being translated into German — hoping we can somehow get a foothold over in Europe. I have a pretty decent stack of uncollected poems to try to do something with, and at some point after all that, I’ll get into one of my other novel projects. And I really miss painting, so I better find a way to do some of that too.

Q. Did you continue writing poems while drafting your novel and if so did you find yourself playing off of some of the themes you were tackling in the book?

I definitely did, but as the book got closer and closer to a final draft, I wrote less and less poetry. So I can’t say there was a lot of obvious cross-over. I think there might’ve been more, had I not stumbled on to the collage cover idea. That took up a lot of my not-working-on-the-novel time. That, and the agent search — which, again, is the worst thing ever unless you have a very specific book that fits perfectly into a very specific part of big bookstores! If you have that, that’s half the battle right there.

Q. What are you currently reading?

I’ve usually got a mess of books going: Right now it’s Tony O’Neill’s Black Neon, the short short collection The Late Season by Stephen Hines, Russ Litten’s prison/ghost story Kingdom, and this whip-smart book about sex called Action by Amy Rose Spiegel. I’m a slow reader, and a re-reader, so it never feels like I’ve got the time I need. Poetry is such a treat because I can gobble up a couple poems in a few minutes, but jump back in re-reading the ones that really grab me. I usually keep books like that going for a long time. I have a Huffstickler book, Why I Write in Coffee Houses and Diners — hell, I jump in there to read a poem called “Arby’s Brenda” just about every time I pass that book.

Q. What would you tell a writer who is just starting out?

I guess I’d tell them to decide early on what kind of writer they want to be, what success would look like for them individually and specifically. Without that kind of focus I think it is just too easy to not be able to appreciate the big steps you make along the way, or to dismiss or discount them as not enough.

I’d say put out the very best work you can every time you put something out.

Buy stuff from fellow writers, presses, and artists you like, including extras to give away. Way too many people still don’t know there are ways to get books that don’t involve Amazon or shopping malls.

Don’t compromise yourself artistically. You can never take compromises back, and they lead to mediocrity.

Last, figure out what works for you, and ignore everything that doesn’t.

Hosho McCreesh is currently writing & painting in the gypsum & caliche badlands of the American Southwest. His work has appeared widely in print, audio, & online.