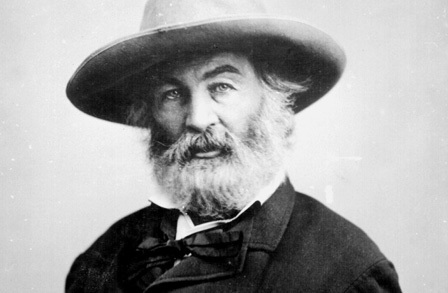

(In their introduction to an anthology of 100 poems, Visiting Walt: Poems Inspired by the Life & Work of Walt Whitman, the editors, Sheila Coghill and Thom Tammaro, explain his enduring appeal. Here’s an excerpt.)

1865. Leaves of Grass. Has there even been a year or a book—before or after—so important, so vital, to the life of American poetry? And Walt Whitman. Has there ever been a poet—before or after—so central to the life of American poetry? Consider him sensational, mystical, erotic, and expansive; consider him the good gray poet, the moral crusader, the prophet of Democracy, and the enemy of social injustice; or consider him libertarian, lecherous, homosexual, perverted, unsavory, inconsistent, passionate, macho, masculine, feminine, androgynous, rebellious, ideological, controversial, or subversive (of course, he is all of these and he was aware of these assesments in his own time)–there is no getting around his genius for liberating poetry from the stultifying “emotional slither” (Pound’s indictment of Victorian poetry) of the nineteenth century. Whitman is the architect of American vers libre. As Annie Finch has written in her intriguing study The Ghost of Meter: Culture and Prosody in American Free Verse, “For American poets in general, Longfellow’s hexameters [in Evangeline] and Whitman’s triple rhythms were crucial in establishing a new freedom of resources, an enlarged metrical vocabulary. Remarkably quickly the ‘new’ metrical mode came to carry a connotative weight capable of balancing the four centuries of iambic pentameter’s hegemony.” Whitman holds the door open for generations of writers to pass through as they “simmer” their way toward true poetry. This anthology, we hope, represents a diverse group of writers who have come to terms with their “pig-headed father.”