By Karlie Flood

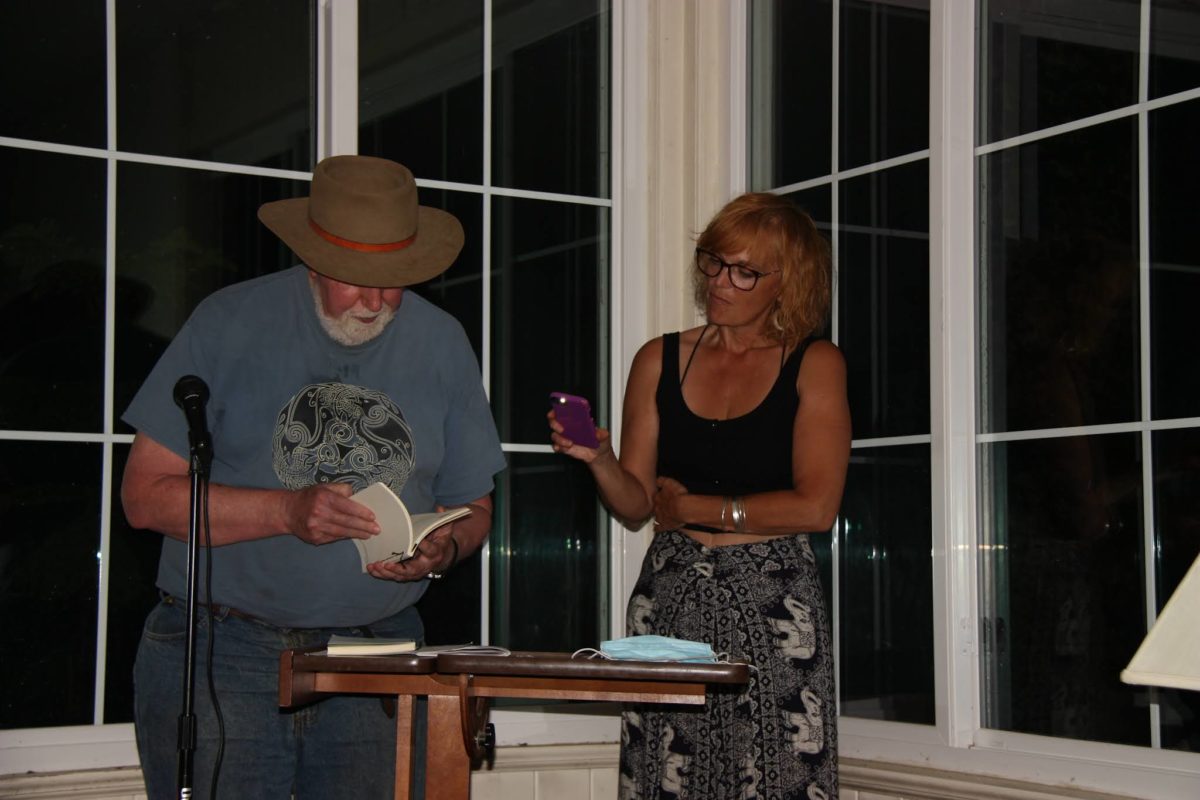

Elizabeth Acevedo walked onto stage with flowered pants, wild curls, and Converse, visiting the University at Albany as a part of the Writer’s Institute Visiting Writers Series on September 6th, 2018. She began her set with a poem.

[Excerpt] “We were not worthy of being the hero, nor the author, but we were always Medusa’s favorite daughters/of ‘serpent curls’ and hard-eyed looks, dreaming in the foreshadow/we composed ourselves since childhood/taking pens to our palms, as if we could rewrite the stanzas of lifelines that tried to tell us we would never amount to much,” Acevedo vocalized. As if nothing happened and she did not just warrant her place on stage and demand our full attention, she sat down and casually asked: “UAlbany, how ya’ll doin?”

The author and slam poet earned her MFA in Creative Writing from the University of Maryland. She remembers being the only person of African descent in her classes, meaning she was often the darkest person in room. She was also the only person from a major city who wrote about growing up in a city. When she turned in her assignments, all the Spanish words had question marks, and the slang had circles around it; “I didn’t always get the generosity from my readers of ‘we’ll do the work to meet you on the page.’” She recalls feeling alone throughout her graduate career. Acevedo faced a lot of doubt from herself; “I didn’t know if I was a poet. I didn’t know if I was a writer, if I deserved to be in that space, because I felt like every workshop was reinforcing, ‘I don’t actually know if I have a story to tell, because nobody gets it,’” she said.

She was deciding whether she was going to leave the program when her professor walked into class one day, gushing about “the most amazing poem” he had just read about deer. Acevedo quickly adds that she has “no beef” with deer; “I think venison is delicious—I’m not hating on anybody’s wildlife,” she said laughing, but refocuses the audience to what troubled her about her professor’s reaction. The deer reminded her of the dominant and reoccurring stereotype about what poetry should be: “flowers, clouds, and deer,” as Acevedo describes it. The professor instructed everyone in the workshop to write an animal ode. Everyone in the class had a “proper” or “beautiful” animal—from blackbirds to sea anemones—but when the professor came to her, she paused. She had always been told to “write what you know.” Because she grew up in a big city, what she knew happened to be rats, and lots of them, so she told the class she would write about rats. To this, her professor responded, “rats are not noble enough creatures for a poem. Liz, I think you need more experiences.”

Even years later, the shock of his statement had not left her. “As if this man had any insight into the experiences I may or may not have had, just because I’d never gone camping,” she said. She questioned her professor’s belief that there were certain things you wrote about, and certain things you didn’t. This was the moment she realized that “maybe this was not [her] audience, but that did not mean [she] did not have an audience.” She pushed through her doubt, passionately believing that there was a story in her worth telling. She questioned the authority of who decides the people who have a story to tell, and what the boundaries of poetry are. She then delivered what she deemed an “official clapback” to her professor, to all the “rats in the room,” or “anyone who has ever been told they are too small, or too ugly, or too different.”

[Excerpt from A Rat Ode]

“Because you may be inelegant, simple,

a mammal bottom-feeder, always f***ing famished,

little ugly thing that feasts on what crumbs fall

from the corner of our mouths, but you live

uncuddled, uncoddled, can’t be bought at Petco

and fed to fat snakes because you’re not the maze-rat

of labs: pale, pretty-eyed, trained.”

Acevedo credits her “teachers,” rap artists she grew up with like Nas, and J. Cole, who instilled in her the importance of believing in herself. She calls rap her “first writing workshop,” and believes it was hip hop that taught her the mindset necessary to succeed, the idea that “maybe I’m not supposed to be here, but I’m going to act like I am,” Acevedo said. “You can’t teach that.” Acevedo references Dr. Rudine Bishop, a children’s book author, who taught her that “all literature should be a mirror, not only an opportunity to see yourself but also a window; an opportunity for someone to feel and experience something different than their own.” Acevedo grew up reading “nothing but windows” and learned a lot about the world, about American history and culture, but she “never, ever saw [her]self.”

“To come from a background where literary figures are few and far between, there is something to be said about what representation does. To hear that your story that you wrote in the dark, that you didn’t think anyone else would want to read it, helps someone else find themselves in those pages and feel permission or feel less alone, that’s a powerful thing. For me, writing this novel was an attempt at being a mirror. I am going to write myself if no one else will write me in a way that feels precise or feels accurate,” Acevedo said.

So, she followed Toni Morrison’s advice to “write the story you most wanted to read;” a story that quickly became a New York Timesbestseller titled The Poet X.A coming-of-age story told entirely through poems, The Poet Xtraces the life of Xiomara Batista, a 16-year-old, Dominican-American from Harlem, and her journey to slam poetry. Acevedo navigates through the pressure of parental expectations, first loves, and religion while discussing difficult subjects such as rape culture, gender roles, and the process of second-guessing truths that were once perceived to be cemented. The poems are beautiful; a collection of sonnets, haikus, reactions, and conversations fill the pages. It was musical. Heart-wrenching. But most importantly, it was real. She did not shy away from the messy parts of growing up, and what it was like to grow up Dominican-American.

On stage, Acevedo spoke with passion, poise, and sophistication. One moment she was soft-spoken and laughing, and the next she fiercely challenged upheld societal beliefs. She demanded respect and she earned it. Acevedo closes her performance with a rap verse, dedicated to “Young Liz.” She is a powerhouse, reminding every single one of us that we all story to tell if we believe we do. And to the “rats” of the world: “we are worthy of every poem.”