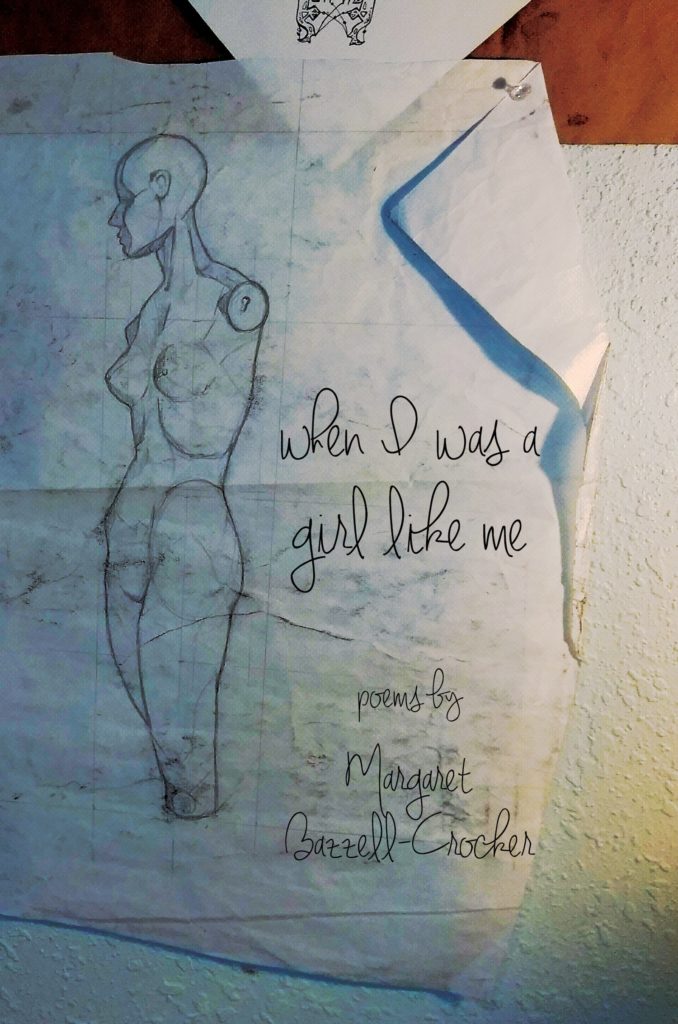

Q. When I Was a Girl Like Me is the first book that you have published in years; Were you writing during the hiatus? What other artistic outlets were/are you involved in?

These poems span the years of my publishing hiatus, really, from almost twenty years ago to now. I’m an incredibly undisciplined writer in that I don’t sit to write regularly at all. I have a family, a job that takes up a lot of my physical and emotional capacities, a house, pets and life. You know how it is, I’m sure. But, even when I was young, I would get an idea in my head and stew on it for awhile before I would sit down and just plunk out the whole thing. Jason Ryberg and Dan actually gave me the suggestion to publish again, and when I began putting the work together, more poems came to round it out. I didn’t really plan a message, but when I put it all together, the message was there. As far as other pursuits, I do like to paint and redo furniture. I love a good thrift store where I can find things to repurpose. That’s my house, basically. Ten percent hand-me-downs and ninety percent repurposed thrift store finds.

Q. Setting influenced your perspective throughout this collection, but especially in “WE LIVE IN A NEW NEIGHBORHOOD NOW. YOU CAN’T DO THAT SHIT ANYMORE.” This poem resonated with me and especially the epiphany in the end, can you elaborate on the importance of place in your work?

Q. Setting influenced your perspective throughout this collection, but especially in “WE LIVE IN A NEW NEIGHBORHOOD NOW. YOU CAN’T DO THAT SHIT ANYMORE.” This poem resonated with me and especially the epiphany in the end, can you elaborate on the importance of place in your work?

I hope that people get a definite feel for Midwestern sensibility in my poems because that’s been influential throughout my life. Dan and I have moved all over the place and we always seem to come back home to the Midwest, somewhere on a riverbank. I feel like there’s a blunt, spare feeling to my writing and that’s been influenced by where I grew up and the people around me. We don’t mince words here, there’s little bullshit. I kind of grew into my own style after comparing myself to other people who had prettier words than me. I discovered that it’s okay if the language isn’t flowery or even if the poem isn’t necessarily beautiful. I learned to like a powerful sentiment instead, like a Midwesterner who might say two or three words to you that are loaded as hell. You get the gist pretty quickly. My work has also been greatly influenced by the struggles Dan and I have had to better our economic situations. We grew up poor and raised our kids poor, just like I describe in Dostadning. We’re still working every day to keep our heads above water.

Q. “The Duck in the Park” and “U-Haul” are two of my favorite poems. Can you discuss how motherhood has impacted your art?

Oh my god, motherhood has impacted my everything! As a matter of fact, a lot of these poems are an attempt to step outside that realm again for the first time in years and years, to no avail. You see that those two poems crept in, despite my best efforts. It’s kind of like becoming the Pope. Can you ever see yourself as anything other than the Pope after that? Are you ever just Bill? I hope that motherhood has affected my writing in a good way. If nothing else came of it (and of course other great things came of it-two fabulous daughters), I,at least, really honed my ability to be empathic. Can I feel the joy, pain or love of other people? Hell, yes. I’ve done it now for 27 years. I feel every victory and tragedy my girls do, and I know I always will.

Q. The influence of strong women is apparent throughout this collection, can you talk about that?

I was lucky enough to grow up with several strong women in my life, chief of which was my mother. I didn’t think this for a long time. My household was not pleasant when I was younger, and I blamed a lot of that on my mother’s decision to stay with an abuser for many years. I only realized later how caught she was in a perpetuating cycle, and how strong she was to break the chains. As dire as the situations often were, this woman had the most optimism and best sense of humor, ever. She was a pioneer in more ways than one. My mom was the first woman on the St. Louis plumber’s union in the 80’s when my step-father was laid off at Chrysler. She brought home the bacon when that wasn’t a super common thing, and she brought it home by being the first woman in the city to be hired in a traditionally male-centric field. She tells a really good story about asking her coworkers to please take down all the lurid pin-ups in the locker room, as there was no separate locker room for her to change into coveralls in. When they refused, she went out and bought a Playgirl magazine and put her own posters up. The pin-ups were gone the next day. She still cracks up about that.

Q. “Mental Health-Portrait 1” and “Mental Health-Portrait 2” are sketches of your experience working in the mental health field. In addition, you co-host a podcast, sanesplaining, that focuses on mental health and the arts in general. Can you discuss mental illness as a subject matter in this particular collection and how your experiences have informed you?

I’ve often wondered how I ended up with such a long career arc in mental health. I remember the first job I had in the field, at a residential home for children here in Cape Girardeau. I felt instantly that this was my calling, and except for a few really tough days, I haven’t regretted it. I think I can trace my fascination with it back to my sister, Barb, who suffered a traumatic brain injury when she was very young. I was motherly and sisterly toward Barb and I’m sure she hated both. One moment I’d be plotting with her about how to sneak a litter of kittens into our house and the next moment I’d be telling her to chew with her mouth closed. The brain is interesting, to say the least, and the stigmas that surround it are confounding, including the stigmas about developmental disabilities and diagnoses outlined each year in the DSM. We’ve come so far with mental health, and yet, there is still so much farther to go. The prevalence of people on the autism scale is actually helping us to better understand developmental disabilities and mental health issues, and, as unfortunate as the rising numbers are, it’s giving people a first-hand view of the idiocy of a “normal” versus “abnormal” rating scale. What the hell is “normal,” even? I’ve gotten on my soapbox a little, but I do hope that there is a wide span of “normal” scenes represented in my collection, including the poems that are obviously about mental illness.

Q. Sacrifice is a major theme in your work, can you discuss some of the sacrifices you have made and how that has impacted your perspective? Looking back would you change anything?

God, no. I wouldn’t change a thing, and I’m so glad I don’t have the power to. We always talk about what super power we would have, especially after the latest big release of another superhero movie. But, really, haven’t we all wished to take it back several times in our lives? Wouldn’t time travel be our greatest collective wish? I think the theme of sacrifice in this collection mirrors the sacrifices women make just living in a man’s world and the sacrifices I’ve made in my own life, as well. I explore this especially in “I Cannot Live Without You” and “The Art of Acquiescence.” Part of my personal sacrifice stems from motherhood. I’ve willingly given my soul to these two lovely beings, and I don’t want it back. But, part of my sacrifice is unwilling. It is the part that is driven by societal norms, by tradition, by family and by laws, even, to comply. Let’s face it-this compliance is still seen as a natural womanly trait. That’s part of the reason I say, right off the bat in the introduction, that I will be angry and unruly in this collection. I’ll say what I want whether this man’s world is ready or not. All that being said, would my work be as good without that element? I don’t know. I am grateful for my life and the sacrifices I’ve made and the challenges I’ve faced, which definitely inform my work.

Q. In “Dear Mary,” it become apparent how religion has/is a part of your world, can you discuss this more outside of the poem, as the poem itself speaks volumes?

Dear Mary is one of my favorite poems, ever. It starts out so crass and then has that glimmer of hope at the end. It’s like a capsule of my life, and it probably encapsulates my thoughts on religion, as well. I always describe myself as spiritual but not religious, and I think this is apt. I didn’t grow up anything-I wasn’t raised Catholic, Jewish or Baptist (Southern Baptist was the go-to where I lived). I was given the freedom to explore and I did. I’ve gone to several churches in my life. I think my Ma was happiest when me and Barb would explore church camps or vacation Bible schools because we’d be away for a week, bothering Jesus and out of her hair. The more I explored, however, the more churches I crossed off my list. So many were exclusive rather than inclusive, and to me, that’s what I thought a church should be, above all else. I also wrestled with the surety these people had. Everyone seemed to know that everything we were told was correct. I don’t know if there’s something bigger, but I feel there might be. I don’t think there’s a book about it or a prayer that’s going to define it, however. I’m happy wondering about it and questioning. I feel we grow through questioning, so I’m okay with the thought that I’ll never be truly sure.

Q. Are you working on any new work, projects, etc.?

I’m not working on anything right now, but I have ideas. Again, I’m someone who has to stew on things, so this could change suddenly. Right now I’m in full stewing stage. Don’t know what I’ll have to say or how I’ll say it, but I’m sure it’ll come.