Q. Can you talk about the inspiration for Visiting Hours?

I’ve had the privilege of working with incarcerated people for many years now. I taught and administrated with a liberal arts college program for about 8 years, ran an education project with our county jail for another two-plus, and am now back to prison with another college program. Getting to teach, know, and befriend many people behind bars was the inspiration for this collection.

Q. What challenges did you face while writing this collection?

Q. What challenges did you face while writing this collection?

No doubt the biggest challenge was grappling with whether I was qualified to put this into the world. The book mostly consists of persona poems, which means I’m writing in the voices of others, of course. As a woman, could I write in the voice of a man? As a person who has never been incarcerated, could I write in the voice of someone incarcerated? As a white Jewish atheist, could I write in the voice of a devout Christian man of color? You get the picture.

I read and thought a lot about this, the lines between homage, exploration, exploitation, and appropriation, and discussed it with many people of many backgrounds, including many incarcerated and formerly-incarcerated men. I came to the conclusion that if done with respect, research, humility, experience, and input, a project like this COULD be successful. Hopefully it actually is….

Q. Can you discuss your experience with teaching in the prisons and how that influences your overall perspective?

By and large, the people I have taught in prison are more mature and driven and work harder than students I’ve taught on traditional college campuses. They have a hunger for learning that makes working with them a pleasure. The closest equivalent outside prison walls is returning students, who are older and more experienced than usual college students and whose life experience has moved them toward college and made it more of a serious choice, rather than just a step the way it was, frankly, for me. Those elements apply in prison, too. My students are older and more focused than average college students, and college for them propels powerful life changes that are hard to quantify. I find this focus and drive inspiring, and it generally leads to higher-quality work.

Q. Can you discuss some of the misconceptions that people have regarding the prison system?

The notion that everyone behind bars is a monster; that they are all the same; that justice is being served by each unique person’s placement there; that they would never be productive/positive members of society; that they don’t wish to grow and change; that they don’t follow what’s going on in the world outside—these are dangerous myths. We like to believe that anyone we subjugate, human or non-human, is part of a nameless, faceless group that deserves what it gets; that makes it easier for us to continue ineffective, inefficient, oppressive systems. To put it poetically: What a bunch of crap.

Q. What are a couple of things you would like to see change about the system?

We need to do the hard work of figuring out what actually works when a person clashes with the rules of a society, and we need to treat each case individually. It makes no sense that a myriad of situations would funnel people into the same building, the same “correction.” Let’s say there’s a sixteen-year-old boy who’s influenced by a charismatic foster mother to beat up her abuser. On the same prison bus is a forty-year-old man who has serially raped older women for years. Why would these two men end up with the same “punishment”? Everything about the system needs to change.

Q. Can you talk about the process of writing and editing this collection?

For years while I was working in prison, people would ask me if I was writing about it. I wasn’t. It felt too close and also exploitative; I wasn’t there for writing fodder, I was there to teach and optimize students’ experiences. But once I’d left, I felt almost compelled to write about it. I missed working there and was in touch with many people who’d been released, etc., and the issues and memories combined to make the words flow. Because I generally find myself less interesting than others as a writing subject, I didn’t want to write much in my own voice; I’ve always loved persona poems as a way to empathize with, get to know, and respect others, and I use the form frequently. Hence the theme here of an imaginary prison populated by the voices of imaginary men. Of course I draw on the experiences and philosophies of people I have known, but this is a fictional world.

Q. Can you discuss working with Willow Books?

I originally sent this manuscript to Randall Horton because I wanted his opinion on what I was doing; Randall is formerly incarcerated and is a poet and professor; I felt he would be well-positioned to tell me the truth about my efforts. Randall is also the senior poetry editor at Willow. When he told me that not only did I “get it right” but that Willow would like to publish it, I was honored but also surprised. Willow is a press for writers of color, and I’m white. But Randall and the publisher, Heather Buchanan, felt that the book spoke to issues that are salient for people of color and wanted to bring it out. Willow is the perfect home for this book, so I couldn’t be happier about their offer.

Q. Can you recommend some writers who are writing on the same theme that inspired you?

There are obvious responses here, like the magnificent Etheridge Knight, and luminous contemporary poets like Reginald Dwayne Betts and Randall Horton, and there are some off-the-beaten-path inspirations, too. Rene Denfeld, who has worked as an investigator in Oregon prisons, wrote a phenomenal novel, The Enchanted (2014), whose narrator is a Death Row inmate. And Bruce Scottus Reilly wrote NewJack’s Guide to the Big House, which gives advice to the newly-incarcerated. Finally, Matthew Parker wrote and drew a wonderful graphic memoir about his experience with addiction and incarceration called Larceny in My Blood: Heroin, Handcuffs, and Higher Education.

Gretchen Primack is a poet and educator living in New York’s Hudson Valley. She has taught and/or administrated with prison education programs (mostly college) for ten years.

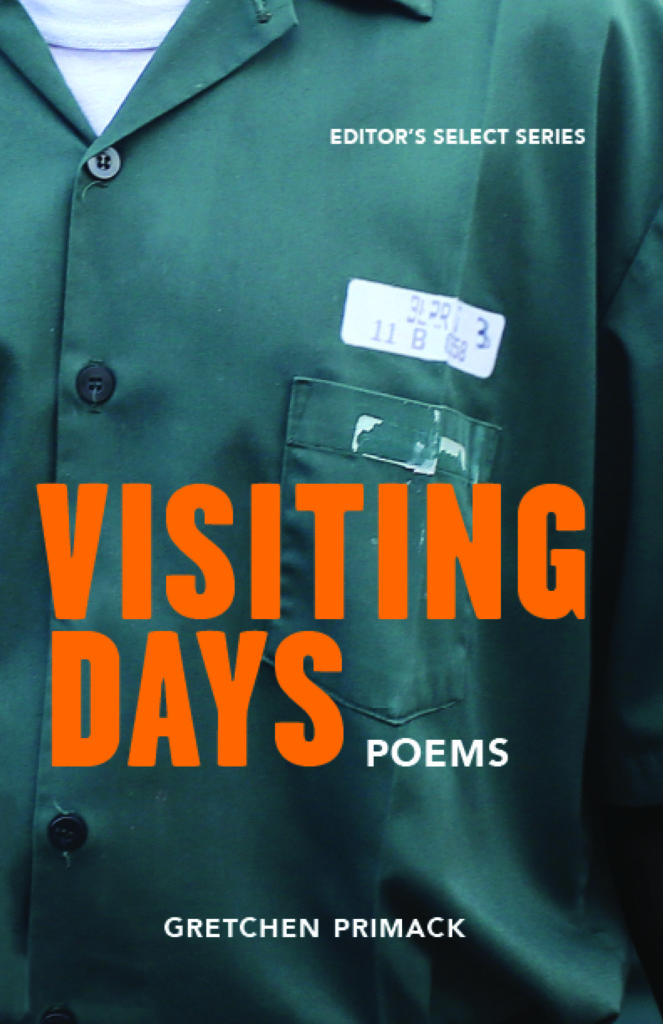

She’s the author of three poetry collections, Visiting Days (forthcoming from Willow Books), Kind (Post Traumatic Press), and Doris’ Red Spaces (Mayapple Press), and a chapbook, The Slow Creaking of Planets (Finishing Line 2007). She co-wrote The Lucky Ones: My Passionate Fight for Farm Animals with Woodstock Farm Animal Sanctuary co-founder Jenny Brown (Penguin Avery 2012).

Her poetry publication credits include The Paris Review, Prairie Schooner, Ploughshares, FIELD,

Gretchen is a passionate advocate for the rights and welfare of non-human animals and lives with several of them, along with a beloved human named Gus.