By Karlie Flood

Edited by Courtney Galligan

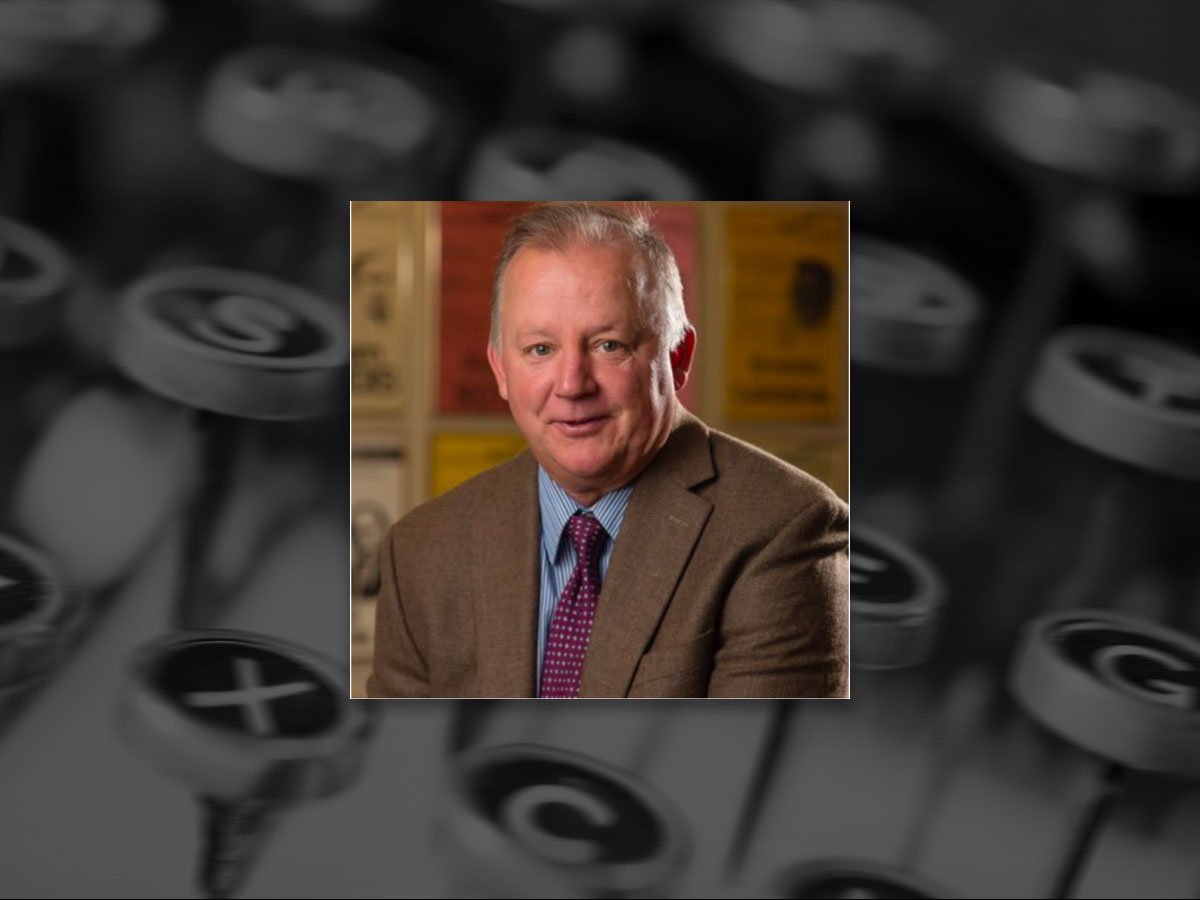

Paul Grondahl, an award-winning journalist, biographer, and now director of the University at Albany’s New York State Writers Institute (NYSWI), and I had a conversation about how he got involved with the NYSWI, his own favorite stories, how he wrote a presidential biography, and why he loves Albany, NY.

Karlie Flood: How did you get involved with the NYSWI?

Paul Grondahl: I came here for graduate school in 1981, in the English department, and then I started writing for Albany Times Union as a reporter. For 33 years, I came to events, and I interviewed dozens and dozens of authors. I always knew about the NYSWI because I was one of their most loyal attendees and I liked to write and interview the authors. When this job became available less than 2 years ago, I applied for it.

KF: And the NYSWI was founded by William Kennedy…?

PG: William Kennedy started it in 1983. He had won the McArthur Fellowship and took some of that money and seeded this. And then he got the president at the time Vincent O’Leary to match him. So, he donated $15,000 a year and he got the president to kick in $15,000 a year, and they started with $30,000 a year.

KF: That’s awesome! What was the original goal?

PG: The goal was to bring some of the great writers around the world to the University. Kennedy was an adjunct professor and he knew some well-known, well-published, prominent authors. He tried to get Robert Coober to come here and he wanted $150 and the English Department said it didn’t have any money. He said “This is outrageous. We need to be able to come up with a little bit of money to bring in great writers.” And so he created this. We’ve had probably 2,000 writers in 35 years.

KF: How do you select the writers?

PG: It’s a long process.

KF: I figured.

PG. Our staff, William Kennedy, we have an advisory group, and a friends of writing group that all contribute. A lot of people with great ideas the challenge is getting people in on certain dates. We work on the academic calendar and we also don’t want to get someone we’ve already had. We’re interested in diversity, all voices, of all forms, and writers from other parts of the world. Sometimes, it’s cost-prohibited, if their fee is too expensive, we might not be able to get them, but we try our best to bring in as many as we can at a very low fee and keep everything free and open to the public.

KF: You write a lot about Albany. What about the city is special to you?

PG: Well, it’s an old city. It was founded over 350 years ago, settled by the Dutch. Albany was important for trade: the Europeans, Dutch, and Native-Americans traded beaver pelts at the time. It’s also the state capital, which makes it important politically. And I think it has a real authentic, not full-of-itself, working class feel to it that I like.

KF: You wrote a presidential biography, right? About Theodore Roosevelt?

PG: Yes. [The novel is titledI Rose Like a Rocket. Grondahl’s books can be found here.]

KF: What goes into that? How do you even start?

PG: It’s a lot of research. I tried to find a niche that hadn’t been completely exploited because there’s been hundreds and hundreds of books written on him, he’s one of our greatest presidents of all time, so I took his early apprenticeship in Albany. He came here as a young man, a couple of years out of Harvard, he was a state assembly member, went on to do a lot of other things, came back as Governor, and then became the president when McKinley was shot and died, and that is when my book ends, when he becomes president. Most of his formative political moments took place right here in Albany, you can walk the streets and go in the same buildings and see the same landscape that he saw.

KF: Did you read other biographies written about him as preparation?

PG: I didn’t. I only wanted to take the early parts—I did read a lot of the standard biographies – but I was only taking him up to the presidency. Edmond Morris, the most famous Theodore Roosevelt biographer, took three books to do his whole career: up to the presidency, the presidency, and then post-presidency. I just took a small slice and focused on his Albany years.

KF: Did you know you wanted to be a reporter coming into college?

PG: Not really…I was an English major. I always liked to read books and write about books and I loved literature. I never took a journalism class. I was an English Literature major—as an undergraduate and graduate student. I liked to write. I wrote for my school paper as an undergraduate at the University of Pugut Sound in Washington. I continued to write, and I got this opportunity to go to graduate school, which was great. I came from the Pacific Northwest and I liked it here. I applied to newspapers and I finally got hired at the Albany Times Union. I started at the bottom, covering shootings, fatalities, crashes, and fires—it was very good training though.

KF: So where did you grow up?

PG: I was born in Seattle Washington and then moved to Tacoma, Washington.

KF: What was it like covering shootings and fatalities? That’s hard to do.

PG: It is. It taught me to be empathic, taught me humanity—there’s nothing worse than seeing a parent and their child dead on the ground or a whole family lose everything in a fire. You learn that life throws you a lot of tough things, and you have to pick yourself back up. Teddy Roosevelt taught me that too—he had a lot of setbacks and he carried on. I think working with the night police I got a lot of empathy for the human condition.

KF: If you didn’t take any journalism classes, did you just learn on the spot?

PG: I did. I learned by watching great reporters and observing and learning from mistakes and working my way up from the night police beat to doing major projects.

KF: It’s different writing in that objective, journalist form than crafting argument in English Literature.

PG: Right. All good writing is storytelling, and research, and getting your facts right, and quoting people correctly. There’s no margin for error—it’s black and white—but everything else is how you craft a story and how you develop it.

KF: And there’s still the same common theme that people have to care about it and be interested.

PG: Yeah. You have to make them sit up and give you five or ten or fifteen minutes of their precious time.

KF: So, how has William Kennedy inspired you as a writer? I know you’ve said a couple times that he’s one of your mentors.

PG: He’s the very first person I met on this campus in 1981, and he sits in that chair right there when he comes in. I just got back from Dublin with him and his family, he got a major award from the President of Ireland. It was amazing. He taught me work ethic. He’s still working. He was working on the plane coming back. I was tired, I was sleeping, and he’s almost 91. He’s dedicated to the craft of writing and that’s why we have this great writer’s institute, because he thought it was important to learn from great writers.

KF: You said he was a professor, right? That’s how you met him?

DG: That’s how I met him.

KF: Did he write for a newspaper too?

PG: He wrote for the Times Union, too. In fact, I’m doing a great event on December 17 at the Times Union with two of my mentors, Bill Kennedy and Harry Rosenfeld—he’s the editor of the TU, he hired me—and Rex smith. We’re going to have a discussion between the three of us: Times Union alumni, who went on to write books. I learned a lot from both Bill Kennedy and Harry Rosenfeld and other great professors I’ve had. I always tell my students to find a mentor. Bill Kennedy was my mentor. He wrote the introduction to my first book. He was always encouraging if I sent him any of my writing, and he would invite me to have a drink after all these writer’s institute events. I got to know him and his family, very well.

KF: That’s important to have someone like that. Who’s the other guy you mentioned?

PG: Harry Rosenfeld, he’s the editor of the Times Union. He was the editor of Woodward and Bernstein at Washington Post. [You can see him in All the President’s Men, played by Jack Warden.]

KF: What has been your favorite article to write or something that has stood out to you?

PG: I got a lot of response on this long series of articles I did on Poppy—that was his nickname—his name was Samuel Baez. He was homeless, addicted to drugs, mentally ill, but there was a lot of intelligence and goodness and resilience in him. I sort of followed him around and wrote many stories over the course of several years. He had a whole family out in Arizona, and he had moments of sobriety, but he never quite got his life together. He ended up dying. I wrote his obituary, but I got to know him. He was emblematic of a lot of people you see on the streets. I did a lot of prison coverage, prisoners in solitary confinement. I try to write about people on the margins, who don’t have a voice.

KF: Did you come up with that idea, about Samuel Baez?

PG: I met him when my daughter was in middle school. I took her and her friend—they had to volunteer at a soup kitchen – and I served him lunch and got to know him. I finally went to find him, and I had this long relationship with him. It usually wasn’t good—he would get beat up or thrown in jail, he’d end up in a homeless shelter, and then he’d get his life together and have an apartment and have a job for a little while, and then his demons would catch up to him. It was about 20 stories. Homeless people are kind of invisible sometimes. People tend to look past them. It’s a very difficult problem.

KF: What’s the most important lesson that you’ve learned in your career so far?

PG: To keep going. Not every story is perfect, there’s no such thing as the perfect book or the perfect article so you kind of have to do your best with your deadline and move on. Accept that you’re always growing and hopefully you get better with each article, each book, each year.

KF: Do you prefer one sort of writing over the other—like books or articles?

PG: I think it’s all somewhat the same. I try to throw myself in and do my best, no matter what the subject is, whether it’s a small story or a larger story. A lot of it is being curious, being interested. I’m a people person; I like meeting people and hearing their stories and then sharing their stories. Most people can’t tell their own stories. They lack either the writing skills or time, so it’s a privilege to be able to tell someone’s story. I write lot of obituaries and the families are so thankful. It’s kind of the last word on somebody’s life. Sometimes a long, accomplished life and sometimes a short, tragic life. I did a long a series on opioid and heroin addiction, and those were a lot of sad stories about young people who died of overdoses. To be able to tell a person’s story and capture life in one article is something that families are often thankful for.

KF: How do you do that—tell someone else’s story?

PG: You talk to a lot of people. The best writing has the best reporting. A lot of young writers think, “Oh, I’ll talk to one person.” If you can get 10 people that know this person, coming from every angle and facet of their life, it makes for a much better story.

KF: This is my last question. Do you have any advice for young writers?

PG: Start writing and get published and let people see your work and comment on your work. Find a community of writers that are interested in the same things you’re interested in and bounce ideas off each other. The great thing about a newspaper is that it’s collaborative. Every day, everybody has to do their job to get the paper out. There’s a lot of interesting and smart people, and it’s a lot of fun to be around where sparks are created, and connections are made. It’s the same thing with writing; find your tribe.

Visit https://www.nyswritersinstitute.org for the incredible Spring 2019 that Paul and his team have compiled for Albany and the surrounding communities.