Q. Your new chapbook “GROWING UP BLACK” discusses the complexities of coming of age in a society where the color of your skin alone defines you, can you discuss some of the challenges you faced when writing these poems and when deciding to publish this collection?

One of the challenges was looking back at many of these experiences from an adult perspective and seeing how these events shaped my life. When I was a kid, I didn’t fully understand their significance, which made writing some of the poems difficult. Growing up, I just assumed that people calling you racial slurs or treating you differently based on your skin was a part of life. And it was (and is) for many minorities in America. So, I tried to stay true to the event/experience being depicted while overlaying it with the perspective I have now. It was a balancing act to showcase the experience as it was while trying to connect it to a larger theme in our society.

As for publishing the collection, the more difficult part was selecting the poems and title. Like most writers, I thought about the themes I wanted to convey and which poems best allow for this. But being black, I was more cognizant of the work I included. Minorities are often treated as a singularity in that one represents the many. This is true whether it’s race, gender, sexuality, or socio-economic status, so I wanted to be mindful about how I depicted the speaker, grouped the poems, and what poems I included. I wanted to showcase that these were experiences unique to an individual but that they’re also connected to a larger community.

Q. In many of the poems you discuss family secrets, did you have trepidation when including these pieces in the collection?

I did have some concern about how my family would react to these poems, but my family doesn’t know about my work, so I feel like I can be a little more open about this. But they all overcame a great deal of adversity and broke several barriers in their professional lives, so I understand why they want to cast the image of “perfection,” but I’ve seen how keeping secrets buried can destroy lives at the same time. I reference this a little bit in my poem “Funeral.”

Q. Another idea you discuss in several poems is wanting to change your skin color, so you can be accepted, you write, “One night I carved my thin arms/to peel away layers of history./so I could turn white and be with her.” lines like these standout, I can’t imagine it was easy to say this, to be so open and honest, can you discuss this strength of yours, your ability to say the unsayable?

Q. Another idea you discuss in several poems is wanting to change your skin color, so you can be accepted, you write, “One night I carved my thin arms/to peel away layers of history./so I could turn white and be with her.” lines like these standout, I can’t imagine it was easy to say this, to be so open and honest, can you discuss this strength of yours, your ability to say the unsayable?

I never really thought that I write the unsayable. It was simply what part of my life was like. I grew up in a predominantly white community in the 80s. It was hard wanting to be someone else, to want to change yourself to fit into the world around you. It took me years to realize that it wasn’t worth it and to accept myself. So in a way, writing these types of poems was easy in the sense that it felt like they were about a different person.

Q. In “Black Man Poetry,” you write about how skin color has influenced your writing, can you talk about this as this piece touches upon a complex discussion that should be had more often in the literary world?

Nikki Giovanni’s “Nikki-Rosa,” which has had a profound impact on my writing, addressed this in the late 1960s, and the conversation is still taking place today. There are some editors who “welcome” work by people of color and other marginalized groups. However, they don’t necessarily want work by minority writers per se; rather, they want the work to demonstrate the struggles and strife of being a marginalized member of society. In doing so, it fits a narrative within the literary world that has been in place for decades. It’s an easy trap to fall into, and one that happens for various reasons.

Q. One of my favorite poems in this collection is “Gravel Parking Lot,” where you discuss being with your children at a diner when two men, who drove up in a truck with a confederate flag, come in and join three other men. You talk about escape and how different it is now that you have children, you write “And I would still have to get my kids to the van,/ make sure they were buckled in their car seats/ and their favorite Disney song is playing.” Can you discuss how having children has influenced the way you see the world and in turn the way that you write about the world?

I constantly wonder what type of world my kids will ultimately live in. Their upbringing has been much different than mine, and society has become more diverse since I was a kid. But you never know how they’ll be treated or how resilient they’ll be to the harshness of others. Because of this, I think this concern has certainly filtered into some of what I write about—this sense of questioning and whether or not they’ll have similar struggles like I had.

Q. What projects are you currently working on?

My father passed away about three months ago, so I’ve traveled throughout the Midwest taking care of his Estate. I’ve gotten to know several people from South Dakota to New Mexico who knew him, and I’m getting a fuller picture of who he was as a person that I didn’t know as his son. I’ve been writing about this lately–small towns of America, the types of people who live there, and what it means to lose a parent. I don’t know if it will turn into anything or not.

Q. How did the 90s zine scene influence you and your writing? How does it compare to the current writing scene?

I arrived to the 90s zine scene kind of late. But when I first started writing and wanting to get published, I read many of the mainstream magazines. I found the work they published didn’t really fit my style or what I was interested in. I was looking for something with more grit and dirt and rawness. Then I was introduced to small press magazines, and a whole new world opened up. I felt connected to a community that didn’t want to fit into the mass market and experimented with not just defining what poetry is but what poetry is about. It was that counter-culture I was pulled to. And I see a lot of comparisons now with online magazines and that people want to carve out a niche for themselves and their voice. This, coupled with social media, allows even more poetry to be shared with a wider audience, which I think is great.

Q. What are you currently reading and or who are some of your favorite writers?

Right now, I’m reading a bunch of freshman composition papers, and I don’t think I could list my favorite writers because I know I’d forget someone. But when I think about the writers who have influenced my writing, I would have to say people like Nikki Giovanni, Lucille Clifton, Sherman Alexie, Charles Bukowski, and of course Dan Crocker.

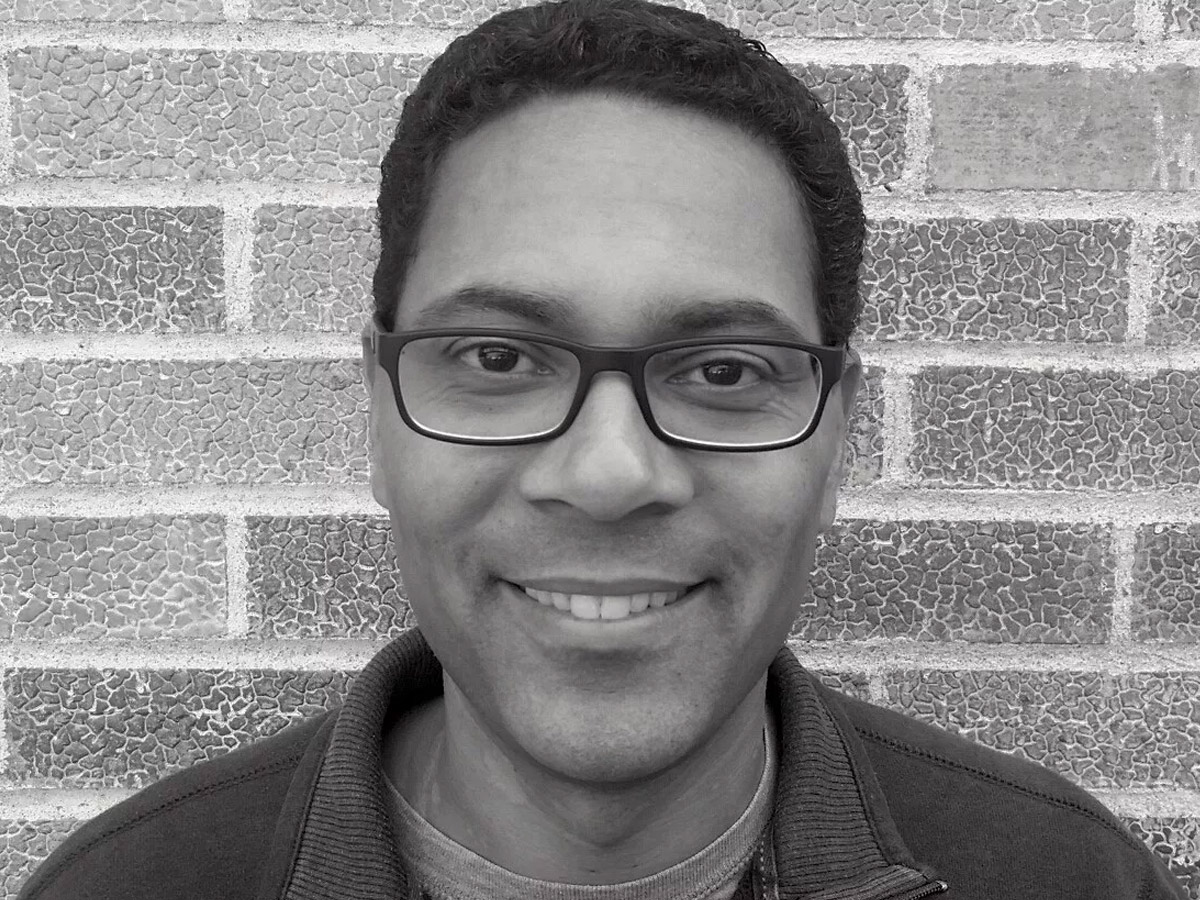

David M. Taylor’s work has appeared in various magazines such as Albany Poets, Califragile, Misfit Magazine, Philosophical Idiot, Rat’s Ass Review, and Trailer Park Quarterly. He has been a featured poet on KRCU’s “Poetry on the Air” series as well as a judge for several literary contests. He was also a finalist for the 2017 Annie Menebroker Poetry Award, and his most recent poetry chapbook, Growing up Black, was published by CWP Collective Press.