By Jeff Doherty

The Stephen A. DiBiase Poetry Prize is an international prize devoted to poetry. There are monetary prizes for different levels of poetry, but I wasn’t interested in following the money; I wanted to know who created this prize, why it was created, and to find out who Stephen A. DiBiase was. Above all, I wanted to know what made it different from the numerous other prizes I’ve found online. I got to talk to Bob Sharkey, the man behind the prize’s creation, and learn about the storied past of Sharkey, DiBiase, and the tenets of the prize itself.

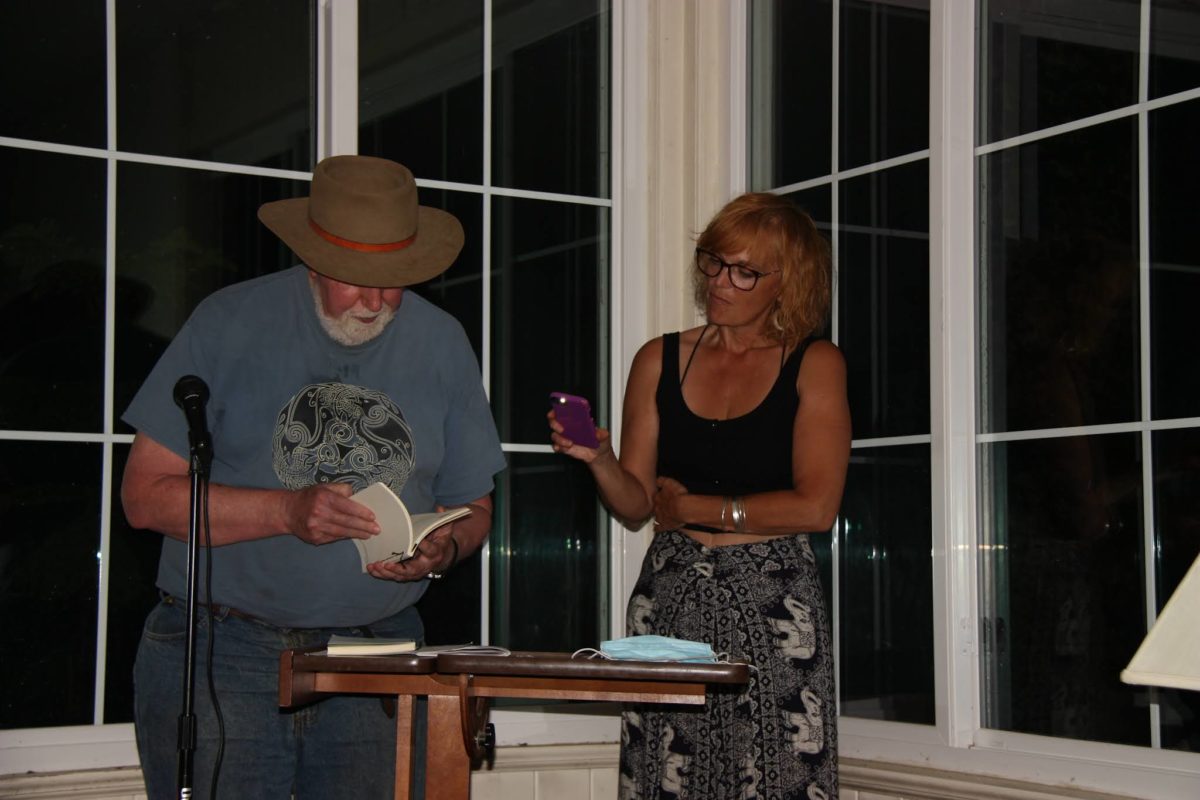

Sharkey joined the Capital Region poetry scene in 2001. He went to various open-mic nights, and has done a number of featured readings on the board of the Hudson Valley Writer’s Guild, of which he is currently a member. As he observed open-mic and poetry contests he found didn’t like the way many of the prizes were designed. He decided to create his own prize with his own rules.

Sharkey’s original conception for the prize didn’t start as a memorial to DiBiase. “When I conceived the idea of having a contest, first of all, the main driving force was that I wanted to give something back to the local writing community,” Sharkey said. The ground rules for the prize were different from other poetry contests. There are no specified line limits or page limits. Published and unpublished work can be submitted. There are no age limits either, “We get poetry from everyone ages 11 to 91,” Sharkey said. Poetry submissions come from all over the world. There are four judges each of whom are winners from past contests; this allows for a wide range from multiple poets leading to a greater variety of poetry being prize worthy. Sharkey’s role as the contest’s creator is to be the curator of each vast pile of poetry that a chosen judge will read.

Sharkey said he is open to any kind of poetry from abstract pieces to ones written in a formal style. “I try to balance things,” Sharkey said. The prize also doesn’t publish any of the work allowing winning work to be syndicated. Prize winning poetry is read aloud at the finalist readings. Poems that have done well in the past were poems that were: “Very well written, had strong imagery, with very often a very personal angle to them,” Sharkey said. The poem can’t be written just for the sake of putting words on a page. No matter how abstract the piece is it must convey something to whichever judge ends up reading it. There are also three tiers of contest winners which allows for a wider range of poets to win a prize for their writing. A current judge and prior winner, Martin Willetts had written a long piece in an informal style about the way in which he has dealt with his own experiences in Vietnam. Willetts gave intense power to his words, like the other current judges, making them winners through their own style of writing.

The conception of the prize came after a long 25-year career of writing for the New York State Department of Social Services. Sharkey wrote as part of the policy unit. “Writing regulations was probably the closest thing to poetry,” Sharkey said. “You have to be very precise, and weigh each word, put your commas in very carefully.” He had written poetry since he was a young boy, and felt lucky to keep writing when he got his Social Services job. Much of his work was focused on cash-welfare programs, constant correspondence with the state government, and policy research

When he wasn’t writing regulations he wrote instruction manuals, briefs, and even wrote with the aid of lawyers to make sure his work was on point when it came to the facts at hand. He had an incentive to “maximize the federal dollar,” and make sure each cent was put to use somewhere within the state. Much of that maximization was visible to him as he frequently traveled to places, from homeless shelters to soup kitchens, where his policy had made an impact.

Sharkey talked about the namesake of the prize, Stephen A. DiBiase. “He was my first friend really,” Sharkey said. They both grew up in Portland, Maine, and DiBiase was a kind of older brother figure to Sharkey. Even after they had gone on to different high schools they kept in touch. When the Vietnam War began DiBiase was deployed, and in turned convinced Sharkey and a number of other friends not to go to war; he helped them get conscientious objection waivers. One of the men among this group ended up in federal prison. DiBiase, a US Army vet, died in 1973 by drowning under odd circumstances. Therefore, when it came to naming the prize, Sharkey said, “I had been thinking about what to call this thing. We [Sharkey and his wife] had been talking about this thing. We were remembering something about Stephen, and it was a natural thing to name it for him. I think about him a lot anyways.”

Sharkey wants prize goers and listeners at the prize readings to remember DiBiase as, “A true friend. Someone that tried to do the right thing, and was very supportive of his friends. Not only me, but his other friends… someone who in his very short life was vital,” Sharkey said.

Submissions for the prize are accepted up to January 15th, with the reading of finalist pieces in May of next year. On Sharkey’s Facebook he displays a list of finalists describing a portion of 255 entries from 33 countries with the prize winners syndicated on a number of literary sites.

Sharkey’s life and his love of poetry have come together after years of hard work to form this prize in memoriam to a great friend. This memorial is fitting in many ways including the fact that DiBiase was also a writer and had written for his school newspaper. Now he is remembered not only for the rich yet short life he lived, but for the prize given to poets who touch the hearts of their readers with their own rich, and sometimes sad tales. This prize gives poets a freedom to write, submit and win no matter how old they are, where they come from, or how they express it; that is the Stephen A. DiBiase Poetry Prize.